One of the biggest puzzles in archaeology is the pyramids’ near-perfect alignment to true north. Known as the pyramids alignment mystery, it’s baffled researchers for decades. Now, a modern engineer thinks he’s cracked it—using nothing but a stick, a string, and the autumn sun.

Not just straight—but nearly perfect

Out of all the mysteries surrounding the Great Pyramid, its alignment is among the most precise—and least explained. Each of its four sides faces a cardinal direction with astonishing accuracy. The error margin? Less than one-fifteenth of a degree.

This isn’t a fluke. The same uncanny alignment appears in two other massive pyramids: Khafre’s at Giza, and the Red Pyramid at Dashur. All three show a slight but consistent counterclockwise offset—subtle, but identical. That tiny twist has become part of the larger pyramids alignment mystery. How did builders over 4,500 years ago, without metal tools or modern surveying equipment, achieve something so exact?

Theories have ranged from the North Star to magnetic fields to pure guesswork. But none have fully accounted for the level of precision—or the consistent deviation. That is, until Glen Dash stepped in.

The equinox method

In 2018, engineer and archaeologist Glen Dash published a study in The Journal of Ancient Egyptian Architecture, offering a stripped-down but elegant answer. According to his research, the builders may have relied on the equinox and the movement of the sun to orient their monuments.

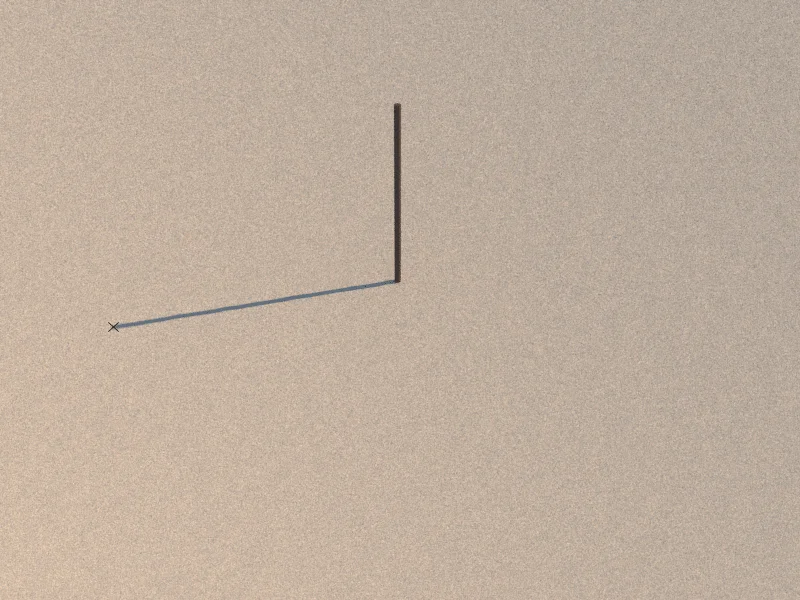

Dash recreated a method that would have been entirely accessible to ancient Egyptians. Using a simple vertical stick—called a gnomon—he tracked the tip of its shadow over the course of the autumn equinox. The result was a smooth arc of points on the ground. By stretching a piece of string between two key points in that arc, he created a line running almost exactly east to west.

“On the equinox,” he wrote, “the surveyor will find that the tip of the shadow runs in a straight line and nearly perfectly east-west.”

That “nearly” is important. Dash’s experiment produced a slight counterclockwise error—exactly like the one found in the three great pyramids. In other words, the same technique used in his modern demonstration might explain how ancient builders achieved their alignment over 4,500 years ago.

Not perfect—but close enough to matter

Until Dash’s experiment, the equinox hadn’t been seriously considered as a tool for alignment. Many scholars dismissed it as too imprecise for monumental architecture. But Dash’s results suggest otherwise. His method doesn’t require any astronomical knowledge, complex instruments, or theoretical math. Just a sunny day and a patient surveyor.

And it works.

The slight offset produced by this method doesn’t discredit it—in fact, it makes it more compelling. That same margin of error shows up in every well-preserved pyramid aligned to cardinal directions, and it leans in the same direction. Coincidence seems unlikely.

This doesn’t solve every aspect of pyramid construction, of course. It doesn’t explain how stones were moved, how internal chambers were planned, or what the monuments were ultimately meant to represent. But it does bring us closer to understanding how the Egyptians aligned these structures with such eerie precision.

Replacing speculation with sunlight

The pyramids alignment mystery has attracted its fair share of speculation. Some claim the pyramids were aligned using long-lost technologies. Others point to extraterrestrial involvement. But Glen Dash’s method doesn’t require any of that. It’s grounded, replicable, and rooted in tools the Egyptians likely had access to.

It’s also a reminder that not every mystery requires a dramatic explanation. Sometimes, the answers are as simple as a stick, a string, and the sun—if you’re willing to watch the shadows closely enough.