Recent research on the megalithic stone monument known as Menga, or the Dolmen of Menga, located on the Iberian Peninsula, suggests that its ancient builders possessed a deep understanding of early scientific concepts, including geometry and friction, long before the time of Euclid, the renowned Greek mathematician and “Father of Geometry.”

The study, conducted by José Antonio Lozano Rodríguez and colleagues, reveals that constructing a monument as sophisticated as Menga, between 3800 and 3600 BCE, would have been impossible without some form of early scientific knowledge. The researchers argue that this advanced understanding challenges the long-held perception of Neolithic societies as primitive.

“Our findings contradict the outdated view of Neolithic societies as unsophisticated,” the researchers state. If confirmed, the insights gained from the Menga monument could prompt a re-evaluation of the origins of early science and provide a more accurate depiction of these ancient societies. These communities, which constructed monumental stone structures long before the Egyptian pyramids, may have been more organized and technologically advanced than previously thought.

For much of the 20th century, scholars generally believed that Neolithic societies, which emerged around 6,500 years ago, lacked the scientific knowledge to construct large monuments. However, recent discoveries, including the ancient site of Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, have prompted a re-assessment of this assumption. These findings suggest that early science may have played a significant role in the construction of such structures.

Earlier this year, evidence from excavations off the coast of Rome showed that Stone Age hunters employed advanced maritime technologies as early as 5,000 BCE. Additional research highlighted how ancient seafaring people used sophisticated technology to colonize parts of Indonesia over 42,000 years ago.

Now, a team of researchers studying Menga has uncovered evidence that its builders likely understood and applied various scientific principles, including geometry and friction.

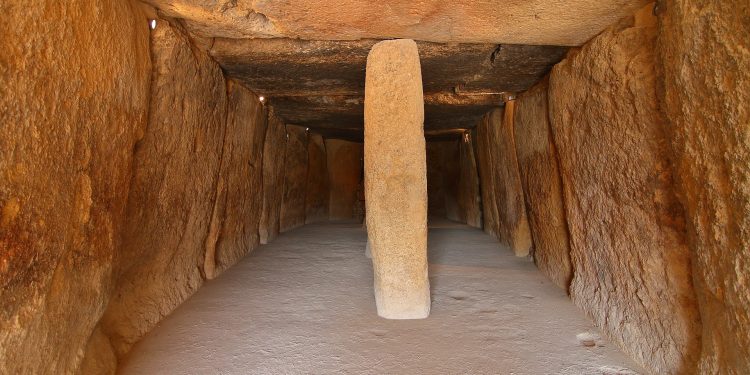

In their study published in Science Advances, the researchers analyzed several key aspects of the Menga site, which comprises 32 giant stones totaling approximately 1,140 tons. The monument features a roof, walls, and pillars, all requiring advanced design, planning, and logistical execution. However, this is the first time Menga has been studied from an interdisciplinary perspective, combining archaeological, geological, and engineering evidence.

The researchers first focused on the size, weight, and composition of the monument’s capstone #5, a 150-ton stone—the largest ever moved in Iberia as part of the megalithic phenomenon. The analysis revealed that the capstones, including this massive stone, ranged from soft to moderately soft. Moving such large and delicate stones would have required at least a basic understanding of friction. The researchers suggest that the ancient builders likely constructed a carefully designed road or trackway to minimize friction during the transportation of these stones.

However, the most compelling evidence of early scientific knowledge emerged from the geometric analysis of the site. The study found that Menga’s builders had a more advanced understanding of geometry than previously believed.

The first indication of the builders’ geometric knowledge came from the site’s upright stones. Inside Menga, the researchers observed that these stones do not stand perfectly vertical. Instead, they exhibit slight slopes and lean against each other at specific angles—80°, 86°, and 88°—on both sides of the dolmen. This positioning creates a trapezoidal shape that enhances structural stability, providing insights into the order in which the stones were placed and how the monument was constructed.

The angular placement of the upright stones likely resulted from the need to support the soft stones used for the roof. This innovative approach allowed the builders to reduce the width of the capstones, which were not very resistant to traction.

Further evidence of the builders’ geometric understanding was found in the way the stones were interlocked through lateral facets. Such techniques were unexpected in a site as ancient as Menga.

Additionally, the researchers analyzed how the upright stones were placed into the bedrock. Both the walls and pillar stones were wedged into the bedrock, indicating a sophisticated understanding of geometry concepts such as balance and counterweights. The study suggests that the builders may have used counterweights to position the stones, highlighting their resourcefulness and engineering skill.

In conclusion, the study reveals that Menga’s builders employed a wide range of scientific concepts, challenging previous assumptions about Neolithic societies. The incorporation of advanced knowledge in geology, physics, geometry, and astronomy demonstrates that Menga is not only a remarkable engineering achievement but also represents a significant step in the development of human science.

The researchers emphasize that Menga’s level of technological sophistication is unique compared to other Neolithic sites. They note that while Göbekli Tepe employed wood and other basic construction techniques, Menga’s builders demonstrated a far more advanced understanding of engineering and science.

“Menga stands out as one of the first monumental buildings constructed with colossal stones, with no known precedents in Iberia or similar monuments in Late Prehistory,” the researchers conclude. “These findings suggest that the builders of Menga were pioneers in early scientific engineering, reshaping our understanding of Neolithic societies.”