In 1799, French soldiers near Egypt’s Nile Delta uncovered a large inscribed slab that would become known as the Rosetta Stone. It contained the key to decoding ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, unlocking the voices of a long-lost civilization. While the stone itself bore no serpent imagery, Egypt’s surviving monuments and tombs are filled with depictions of snakes—coiled, crowned, and sacred. The serpent, in fact, appears everywhere in human history. From Mexico to Mesopotamia, India to Australia, ancient cultures developed strikingly similar snake symbolism. Why?

How could people separated by oceans and millennia independently choose the same symbol to express creation, danger, fertility, and power?

A Global Pattern in Stone and Story

And then it becomes obvious, after just researching a little bit, reading a few aritcles and books, and look at a few illustrations drawn by our ancestors across the globe.

Across continents, serpent imagery appears with remarkable consistency. In ancient Egypt, the cobra goddess Wadjet was a divine protector, often shown rearing up on the crowns of pharaohs. She embodied sovereignty, fire, and the divine right to rule. According to the British Museum, her symbolism reflected both protection and aggression—a duality at the heart of Egyptian cosmology.

In pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, the Aztecs worshipped Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent, a god of wind, learning, and creation. This serpent figure appears prominently in temples and codices, often linked with cosmic order and regeneration. At Chichén Itzá, during the equinoxes, a moving shadow along the steps of the main pyramid forms the shape of a descending serpent—engineered to honor this divine being.

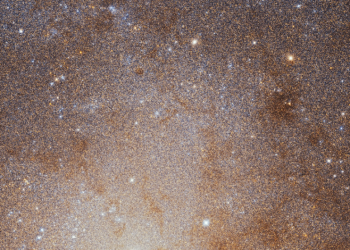

These motifs appear far beyond the reach of shared trade routes or contact. In India, snakes known as Nāgas are still venerated today. In Aboriginal Australia, stories of the Rainbow Serpent stretch back tens of thousands of years, passed down in oral tradition and depicted in ancient rock art.

The consistency of this imagery suggests a deep-rooted psychological or environmental source—but no single explanation has ever fully accounted for it.

From Rock Art to Living Memory

In Western Australia’s Kimberley region, rock paintings depict enormous serpentine figures, their arcs following the curves of rivers and cliffs. These images are attributed to the Rainbow Serpent, a powerful being believed to have shaped the land itself—creating rivers, mountains, and life. Some of these paintings may be over 20,000 years old, though dating remains uncertain. According to Aboriginal elders, the Rainbow Serpent is not a metaphor. It is real, remembered, and revered.

On the other side of the world, early Hindu texts like the Mahabharata describe encounters with divine snakes. These Nāgas are neither wholly evil nor entirely benign. They live underground or near water, protect treasures, and wield supernatural power. Shrines to Nāgas still dot the Indian countryside, where villagers offer milk and flowers to carved serpent stones.

What connects these traditions is not only the snake’s visual presence—but its elevated role in explaining how the world came to be.

Serpents of Kings and Gods

In Egypt, the cobra goddess Wadjet was considered the personal protector of the pharaoh. Her image, known as the uraeus, appears on crowns dating back to around 3100 BCE, during the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under Narmer. Her function was both symbolic and magical—believed to spit fire at enemies and defend the divine order (ma’at).

Mesoamerican texts, such as the Codex Borgia, include detailed illustrations of feathered serpents involved in rituals of time, rebirth, and celestial order. While interpretations vary, scholars agree that Quetzalcoatl’s symbolism was deeply embedded in Aztec spiritual and political life. He was a cultural founder figure, bringing laws, maize, and the calendar.

Despite the wide geographic gap, both traditions elevate the serpent to the realm of divine kingship and cosmic authority.

The Psychological Angle

Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung believed that serpent imagery represents a universal archetype—a symbol embedded in the collective unconscious of all humanity. Because snakes shed their skin, Jung argued, humans instinctively associate them with rebirth, transformation, and immortality. In his Collected Works (Vol. 9), he wrote that the snake’s ability to renew itself made it an ideal emblem of the psyche’s deep structures.

Mythologist Joseph Campbell independently reached similar conclusions. In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, he showed that serpents often play key roles in the hero’s journey—appearing as both obstacle and guide. In nearly every culture he studied, serpents carried the dual symbolism of death and life, fear and wisdom, endings and beginnings.

Psychological theories help explain the emotional power of snake symbols—but they still don’t answer why snakes, above all animals, were chosen in so many places, by so many people.

Environment and Interpretation

Some anthropologists propose that the natural behaviors of snakes made them universally symbolic. In agricultural societies, snakes emerged after rain and often inhabited riverbanks, making them logical candidates to represent fertility and water cycles. In many myths, they are linked to rainfall, drought, or seasonal change.

In ancient Egypt, Wadjet was associated with the Nile floods, which brought fertility to the land. Similarly, Quetzalcoatl was believed to bring rain and agricultural renewal. Serpents in these contexts act as agents of the life-death-life cycle—a pattern at the core of many belief systems.

While no definitive scientific study has mapped all global serpent symbols to specific environmental factors, the correlation between serpent myths and water is notable and persistent.

The Oldest Serpent Yet

At Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey, archaeologists have uncovered serpent carvings dating back nearly 11,000 years. These reliefs appear on massive T-shaped pillars arranged in ceremonial enclosures. The serpents are stylized, elongated, and often depicted in motion—carved with intent, not decoration.

Göbekli Tepe predates writing, agriculture, and urban life. Yet its builders clearly regarded the serpent as important enough to inscribe in stone. While the full meaning remains unknown, the presence of such early serpent imagery suggests that this symbol may have roots far deeper than organized religion or state power.

These are the oldest known serpent carvings yet found, pushing the symbol’s documented history to the dawn of monumental human architecture. And I find it really interesting that the serpent is one of the more prominent symbols at Göbekli Tepe.

So… what the Serpent?

Despite decades of scholarship, the question remains open. Was the serpent a biological fear? A metaphor for transformation? A visual shorthand for cycles of rain, life, and death?

Jung’s archetypes, Campbell’s myths, and archaeological discoveries offer pieces of the puzzle—but not the whole picture. What’s clear is this: across space and time, from desert temples to jungle pyramids to sun-scorched rock faces, humanity chose the serpent. Not once, but again and again.

Whether divine guardian or chaotic force, the snake has slithered its way into our deepest stories—and refuses to leave.