Long before modern clocks and dates, ancient civilizations studied the skies and built ancient calendars that predicted the end of worlds. These were not mere farming tools. Some calendars tracked cosmic cycles stretching across tens of thousands of years, hinting at moments when worlds would collapse, and new eras would rise.

They built monuments aligned to the stars, counted the slow beat of planetary cycles, and recorded time on scales that stretched across millennia.

But to many of them, time was not just a way to organize crops or festivals. Time carried warnings. Their calendars hinted at great cycles — of creation, destruction, and renewal — that could reshape entire worlds.

Today, fragments of this lost knowledge survive: etched into stone, preserved in myths, and woven into systems that hint at an ancient understanding of cosmic change.

Were they simply stories? Or ancient memories of cycles powerful enough to erase civilizations?

The Mayan Long Count a clock for cosmic ages

Among the best known — and most misunderstood — ancient calendars is the Long Count of the Maya. Developed over two thousand years ago in what is now Mexico and Central America, the Long Count was not designed to track a single year, but to map vast epochs of time.

Rather than using months and years as we do, the Maya divided time into baktuns, periods of roughly 394 solar years. Twenty baktuns formed a complete cycle — about 5,125 years.

The Long Count didn’t predict a final end of the world at the close of a cycle. Instead, it signaled a rebirth, much like the end of a season marks the beginning of another. December 21, 2012, a date widely sensationalized as an apocalypse, was simply the reset of the cycle, much as 31 December rolls into 1 January.

What made the Mayan system extraordinary was its precision. Using only naked-eye observations, Maya astronomers measured solar years with a margin of error smaller than that of the Gregorian calendar used today. They also tracked Venus, Mars, lunar eclipses, and likely understood aspects of precession — the slow wobble of Earth’s rotational axis.

Their pyramids and ceremonial centers reflected this cosmic awareness. Temples such as El Castillo at Chichen Itza are aligned so that, during equinoxes, the shadow of a feathered serpent appears to slither down the pyramid’s steps — a blending of architecture, astronomy, and myth.

To the Maya, time was a living force, and the calendar was a sacred tool to navigate an endless cycle of creation and dissolution. Worlds had ended before; they would end again — and each time, the cosmos would be renewed.

The Yuga cycles of ancient India

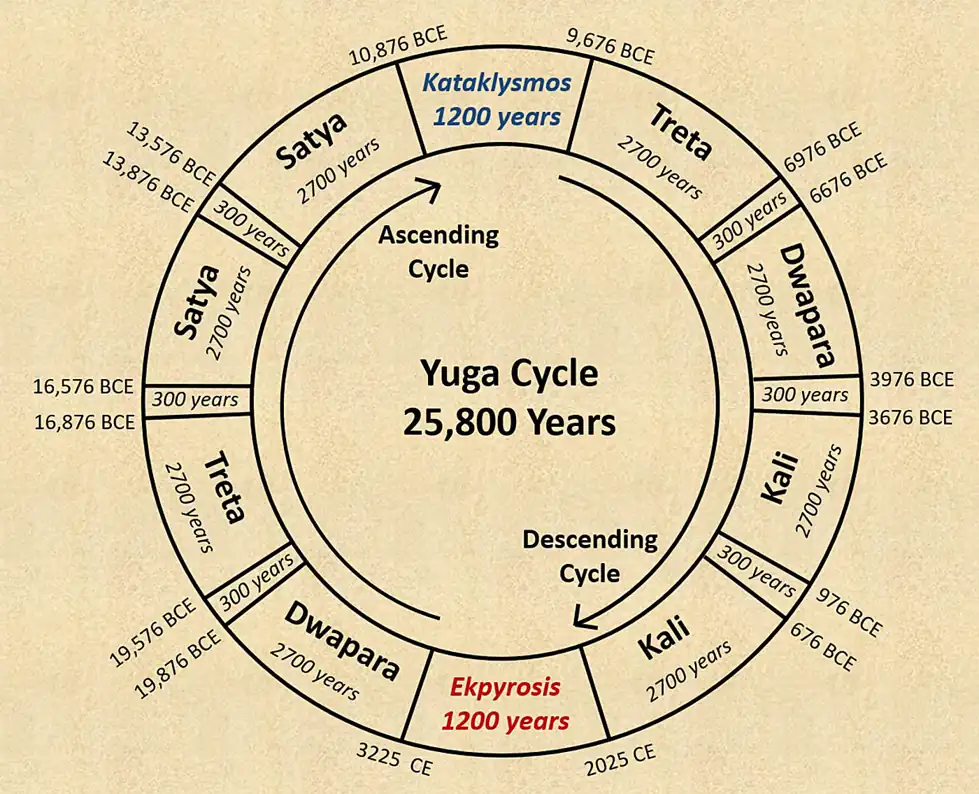

On the opposite side of the world, ancient Indian civilizations mapped time on an even vaster scale. The Yuga cycles, described in Hindu cosmology, divided the lifespan of the world into four great ages: Satya Yuga, Treta Yuga, Dvapara Yuga, and Kali Yuga.

Each age represented a decline from a state of cosmic purity toward deeper materialism and spiritual decay. Satya Yuga was a golden age of virtue and wisdom, lasting thousands of years. Over successive Yugas, human morality and connection to the divine weakened, culminating in Kali Yuga — the present age.

Kali Yuga, often called the “dark age,” is said to be a time of conflict, greed, and disconnection. Ancient texts suggest it lasts 432,000 years, though interpretations vary. Some traditions claim we are thousands of years into this cycle; others argue that its true end is much closer than typically believed.

The Yuga system frames human history not as linear progress, but as a decline and rebirth repeated across vast cosmic epochs. It carries a sobering message: civilizations rise, flourish, and inevitably fall, bound to forces larger than themselves.

Unlike the doom-laden interpretations of modern apocalyptic thinking, the ancient Indian view emphasizes renewal. After darkness comes light; after Kali Yuga, Satya Yuga will begin again.

The Egyptian Zep Tepi the first time

In ancient Egyptian mythology, there is a mysterious era known as Zep Tepi, meaning “the first time.” It was the golden age when gods ruled on Earth, civilization was born, and cosmic order triumphed over chaos.

Zep Tepi was not simply a distant myth. To the Egyptians, it was a cycle that could be reawakened. Each pharaoh’s reign symbolically attempted to restore the original harmony of Zep Tepi, combating the ever-encroaching forces of disorder.

Ancient texts, such as the Pyramid Texts and the writings at Heliopolis, describe times when cosmic balance was shattered by floods, darkness, and upheaval. In these cycles, the Earth would descend into chaos, only to be renewed by divine or heroic action.

Some modern scholars have speculated that behind these myths lie memories of real cataclysms — perhaps ancient climate disasters or massive floods. The annual inundation of the Nile, so central to Egyptian survival, could have reinforced the association between cosmic rhythms and the vulnerability of civilization.

Whether literal or symbolic, the myth of Zep Tepi reveals a profound understanding: order is fragile, and maintaining it requires awareness, action, and reverence for the greater forces at work.

Precession and the cosmic clock

Beyond individual myths and calendars lies a deeper mystery: the possible ancient awareness of precession (Great Year).

The axial Precession — the slow, 25,920-year wobble of Earth’s rotational axis — causes the position of the stars at equinoxes to drift over millennia. Today, modern astronomy tracks this movement precisely, but evidence suggests ancient civilizations may have recognized it long before written science.

At ancient sites like Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, built over 11,000 years ago, some experts believe there are alignments to specific star patterns hint at an astonishing depth of astronomical knowledge embedded within the stones. The builders of Stonehenge, Egypt’s temple of Dendera, and other sacred sites also embedded celestial cycles into stone.

Some researchers argue that these ancient skywatchers understood not only the annual solar cycle but also the slow turning of the heavens themselves. If true, it means that the concept of long, cosmic ages — ages in which civilizations might rise and fall with the stars — was not just a philosophical idea, but an observable reality.

And if you think about it, precession could explain why so many myths from different parts of the world describe repeating cataclysms: floods, fires, shifting skies. These could represent ancient memories of climate shifts and global upheavals tied to long astronomical cycles.

Were these calendars warnings or forgotten wisdom

Modern society often looks at ancient myths and calendars as little more than curiosities, relics from a more “primitive” time. But what if they were something more?

For many early civilizations, calendars were not just ways to mark the seasons. They were survival tools. By watching the sky and recording the rhythms of the heavens, ancient people tried to warn future generations about cycles of destruction and renewal that shaped the fate of the world.

The Maya understood that worlds do not last forever. In ancient India, sages taught that after darkness comes light. The Egyptians believed that without vigilance, chaos would inevitably return.

Today, as we face growing environmental changes, the messages hidden in those ancient systems feel more urgent than ever. Civilizations rise, but they also fall. The forces that challenged ancient societies — shifts in climate, changes in the sky, events beyond human control — have not disappeared. They are still with us.

The way I see this is that ancient calendars were not products of superstition. They were serious attempts to understand humanity’s place in a vast and unpredictable universe. They were messages across time, meant to prepare those who came after. Maybe the real question is not whether the ancient calendars predicted the end of worlds. Maybe it is whether we are ready to listen.