Was there ever an unknown ancient civilization in the Amazon? Hear me out.

From above, the Amazon appears continuous and unbroken. Dense canopy stretches in every direction, with no visible trace of roads, towns, or walls. Only rivers interrupt the green, winding through a forest that seems untouched.

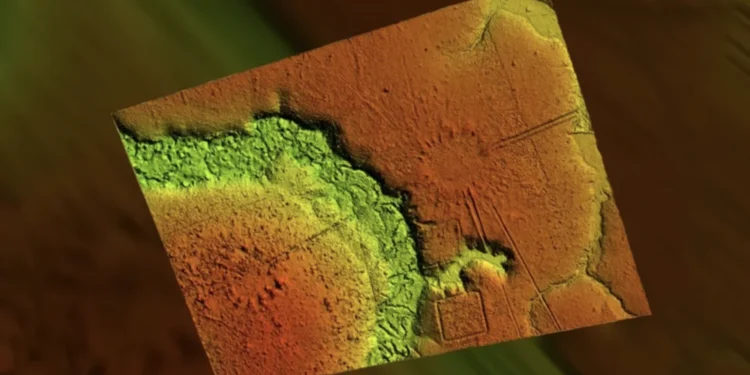

But when LiDAR technology is used to remove the forest from view, the surface underneath tells a different story. Across parts of the basin, the ground is cut with straight roads, enclosed plazas, large circular ditches, and geometric earthworks. These forms are measured, repeated, and aligned. They do not follow the patterns of erosion or chance. They follow planning.

Some sites cover dozens of hectares. Others are linked by raised paths that extend for kilometers. The scale suggests more than scattered settlement.

Rethinking the “untouched” Amazon

For centuries, the Amazon was seen as a wilderness, barely touched by humans. European explorers described thick forests and small, scattered tribes. Later expeditions confirmed this view. They found no stone cities or temples, no written records, no roads or farmland, only isolated communities and a forest that seemed to resist human order.

But earlier accounts had mentioned something different. In the 1500s, explorers like Francisco de Orellana claimed to see large towns along the Amazon River, linked by roads and bordered by cultivated fields. These reports were dismissed as fantasy. The dominant view held that the rainforest’s poor soil could not support agriculture on a large scale, let alone dense population or city building.

The image of a wild, untouched Amazon became an academic fact. The idea of an ancient civilization in the Amazon was pushed to the margins.

LiDAR exposes a buried past

LiDAR, short for Light Detection and Ranging, works by firing rapid laser pulses from an aircraft toward the ground and measuring how long it takes for each pulse to return. In open areas, it maps elevation. In dense forest, it does something more remarkable: it penetrates the tree canopy and captures the shape of the land beneath. When processed, the data strips away vegetation and reveals the raw terrain, down to features less than a meter across.

This tool has transformed archaeology in heavily forested regions, where traditional excavation is slow and limited by visibility. In the Amazon, its impact has been nothing short of revelatory.

Over the past decade, coordinated efforts by research teams in Brazil, Bolivia, and Peru have used LiDAR to scan key regions of the basin. The work is ongoing, but even the earliest surveys changed the conversation. In Acre, western Brazil, more than 450 geoglyphs were identified—massive geometric structures built by shaping the soil into perfect squares, circles, and complex enclosures. These features, often connected by long straight paths, were first spotted in deforested areas but were later confirmed beneath intact forest using LiDAR.

Further south, in the Bolivian department of Beni, LiDAR scans published in Nature in 2022 revealed more than twenty pre-Columbian settlements belonging to the Casarabe culture. These sites were hidden under forest cover, but the scans showed large mounds, platform complexes, central plazas, and long causeways linking settlements across kilometers. Some of the mounds rose over 20 meters and were flanked by defensive ditches and canals. Unlike anything previously documented in Amazonia, these features displayed a high level of planning and construction.

In eastern Peru, similar patterns are now emerging. Preliminary surveys around the Ucayali River basin have uncovered networks of raised fields, canals, and fish ponds, all pointing to long-term human occupation and land management.

What archaeologists are uncovering in the Amazon is not a scatter of isolated villages but networks, and landscapes shaped by sustained human effort. The settlements mapped so far reveal patterns of construction that point to planning across entire regions. Causeways connect one site to the next. Defensive ditches and canals follow coordinated alignments. Plazas, mounds, and platform structures repeat with variations in scale, not concept. These are not random clearings in the forest. They are parts of a larger system built and maintained by organized populations over generations.

These discoveries provide tangible evidence for something once considered speculative: that an ancient civilization in the Amazon modified its environment at scale, building cities, roads, and agricultural systems across a region long believed too hostile to support permanent settlement.

The Casarabe culture and its forest cities

In the Bolivian lowlands of the Llanos de Mojos, a seasonally flooded region once thought too unstable for dense settlement, LiDAR has revealed more than twenty pre-Hispanic sites buried beneath forest cover. These were not isolated hamlets or short-lived encampments. The scans show tiered platform mounds, wide rectangular plazas, elevated causeways, and large reservoirs, built not for survival, but as part of a planned system.

These structures belonged to the Casarabe culture, which occupied the region between 500 and 1400 CE. Their cities were constructed from earth and timber, materials that blend back into the forest over time. But what remains shows scale, repetition, and organization. Roads run in straight lines for up to ten kilometers. Mounds rise in tiers above the wetland floor. Defensive ditches form outer rings around settlements.

Some of the largest sites cover more than 100 hectares. Between them, smaller communities appear at regular intervals, connected by raised paths. This distribution suggests a regional layout, not just individual settlements. The population spread across these networks may have numbered in the tens of thousands, though no definitive count exists.

Earlier assumptions held that the Llanos de Mojos could not support permanent habitation. The Casarabe defied that view by modifying the landscape itself. They raised fields above flood zones, constructed storage ponds, and directed water flow through canals. Their forest cities did not rely on stone, but they were built with knowledge, labor, and long-term intent.

Traces across the Amazon basin

The evidence uncovered in Bolivia aligns with a broader pattern found throughout the Amazon. In Brazil’s Acre state, aerial surveys and LiDAR scans have recorded more than 450 geoglyphs: large geometric earthworks shaped into circles, squares, and intersecting forms. Many of these structures date back as far as 1000 BCE. They are often aligned to cardinal directions and grouped in clusters, suggesting recurring design principles rather than isolated construction. While their precise function is still being examined, their scale and consistency indicate planned effort across multiple generations.

Elsewhere in the basin, other signs of deliberate landscape modification have emerged. In parts of Brazil, Peru, and Bolivia, archaeologists have documented networks of raised agricultural fields, canal systems, and fish ponds. These were not experimental features but large-scale infrastructure. Their design reflects an understanding of seasonal flooding, water management, and soil preservation.

One of the most enduring traces of past habitation is the widespread presence of Terra Preta, or “dark earth.” This soil is markedly different from the naturally acidic and nutrient-poor soil that dominates the region. It contains high concentrations of charcoal, bone fragments, plant material, and organic waste. Created through the controlled use of fire and composting over time, Terra Preta retains its fertility for centuries. It is found in patches across the basin, often near ancient habitation zones, and sometimes in layers several meters deep.

The existence of Terra Preta suggests that farming in the Amazon was not only possible but sustained through intentional soil management. Its spread, coupled with the engineered landscape features, supports the presence of an ancient civilization in the Amazon that worked with its environment at scale, designing for stability rather than short-term subsistence.

Collapse and forest return

The forest did not dismantle these systems. It covered what people no longer maintained.

Following European arrival in the sixteenth century, infectious diseases—smallpox, measles, influenza—moved faster than colonizers themselves. They spread along trade routes and rivers, reaching communities deep in the interior. With no immunity, Indigenous populations declined rapidly. In many regions, the loss exceeded 80 percent within a few generations.

As populations fell, infrastructure fell with them. Roads became impassable. Canals and reservoirs clogged with sediment. Agricultural fields, once raised above seasonal floods, were abandoned and overtaken by vegetation. Without labor to clear and repair, the landscape returned to forest.

Trees grew over plazas. The causeways disappeared beneath vines and soil. Without stone architecture or written archives, little survived in a form visible to later explorers. Most accounts dismissed the forest as untouched wilderness.

Oral memory endured in some communities, but it lacked the physical evidence needed to reshape historical understanding. That evidence remained underground, until LiDAR began revealing the patterns once more.

What counts as civilization

The evidence of an ancient civilization in the Amazon challenges long-standing assumptions shaped by stone-built cultures. In many regions, complexity has been measured by the presence of masonry, inscriptions, and centralized rule. None of these elements are prominent in the archaeological record of the Amazon. Yet the patterns revealed by LiDAR—straight roads, tiered mounds, structured settlements, and water systems, show consistent planning over large areas.

The infrastructure in these regions was made from earth, not stone. Roads were built by raising and compacting soil. Ditches were cut with precision and served as boundaries, drainage, or transport channels. Plazas and platform mounds follow repeating dimensions. These features required organized labor, tools, and long-term upkeep. Their scale and repetition suggest cultural norms that extended across settlements.

In several areas, specific tree species are found in higher densities near archaeological sites. These include Brazil nut, cacao, and palms useful for food or construction. The distribution patterns are not random. Researchers studying forest composition have identified these clusters as possible indicators of past cultivation or forest management. Some trees may have been planted, protected, or selected over generations. These practices shaped the surrounding ecology and altered the forest structure in ways still visible today.

There are no monumental ruins, but the remains are consistent. Canals, causeways, mounds, and engineered soils appear together. The data supports long-term settlement and resource planning across regions previously thought to be sparsely occupied. The evidence reflects systems designed to function within the forest, using available materials and knowledge adapted to seasonal change.

The traces left behind do not resemble those of known empires, but they show sustained presence and control over terrain. What survives is not a monument, like we see elsewhere. What we are seeing in the amazon is a record of construction, maintenance, and adaptation across generations. This, too, fits within the definition of civilization.

What remains to be uncovered

Now there is an unimportant thing to remember. Less than one-tenth of one percent of the Amazon has been mapped with LiDAR. In that limited coverage, archaeologists have already recorded hundreds of geoglyphs, roads, and settlement sites. The findings suggest that large parts of the forest may still contain the remains of pre-Columbian construction, buried under vegetation and unrecorded.

Research teams in Brazil and Bolivia continue to expand the scanned areas. Each survey adds new features, ditches, mounds, causeways, canals, that had not been visible by satellite or ground inspection. In some cases, previously studied sites have been reinterpreted in light of this new data. Patterns have become clearer. Settlements once thought isolated are now understood as connected.

Elsewhere in the basin, sites are being lost. Deforestation for pasture, timber, and agriculture is clearing land faster than it can be studied. Earthworks that remained intact for centuries are being cut through by machines or leveled for planting. In many areas, no record is made before the ground is altered.

The distribution of known sites suggests that the visible record represents only a fraction of what exists. Large regions with similar soil, river access, and forest cover remain unscanned. The scale of human modification across the basin is still being measured. Until more of the forest floor is revealed, the full extent of ancient activity remains incomplete.