There are many desert lines that only make sense from the sky, but why?

Across deserts and high plains, ancient cultures carved massive lines into the Earth. Geometric shapes, animal forms, paths that stretch for miles. From the iconic Nazca Lines of Peru to lesser-known networks in Bolivia and Kazakhstan, these geoglyphs can only be truly understood from the sky. The strange part? Many of them were built long before flight was possible. To this day, no one fully agrees on who made them, or why.

The Nazca Lines — and what we still don’t know

Southern Peru’s Nazca Desert is home to one of the world’s most puzzling landscapes. Etched into the surface are hundreds of perfectly straight lines, massive geometric forms, and stylized figures, all only truly visible from high above. The Nazca Lines. First widely documented in the 20th century, the Nazca Lines are now believed to have been created between 500 BCE and 500 CE by the Nazca culture.

By clearing away the dark, oxidized pebbles of the desert surface, the builders exposed lighter-colored ground beneath, creating images that have endured for centuries in the arid climate. The figures include a hummingbird with delicate wings, a monkey with a curling tail, a giant spider, and even a humanoid shape with large, exaggerated eyes staring skyward.

Explanations for their purpose vary. Some researchers believe they were ritual pathways walked during ceremonies. Others think they may have served as astronomical markers or offerings to deities linked to water and fertility. But even after decades of aerial surveys, fieldwork, and speculation, no consensus has been reached. The full meaning of the Nazca Lines still eludes us.

Bolivia’s Sajama Lines — the world’s largest network

On the high Andean plateau of western Bolivia lies a lesser-known but far more expansive set of lines, the Sajama Lines. Unlike the figures of Nazca, these are strictly geometric: hundreds of thousands of straight lines etched into the ground, forming the world’s largest known network of geoglyphs.

Covering more than 22,000 square kilometers, some of the lines stretch over 10 kilometers in flawless straight lines, even when crossing rugged terrain and slopes. There are no large figures or animals here, just an intricate lattice that defies easy explanation.

Archaeologists believe the Sajama Lines were created by Aymara-speaking peoples, possibly as part of pilgrimage routes connecting shrines, sacred peaks, and burial towers. The sheer number and precision of the lines suggest sustained, large-scale effort over generations. Yet exactly how they were laid out and maintained — and whether their orientation held symbolic meaning, remains unknown.

The Steppe geoglyphs of Kazakhstan

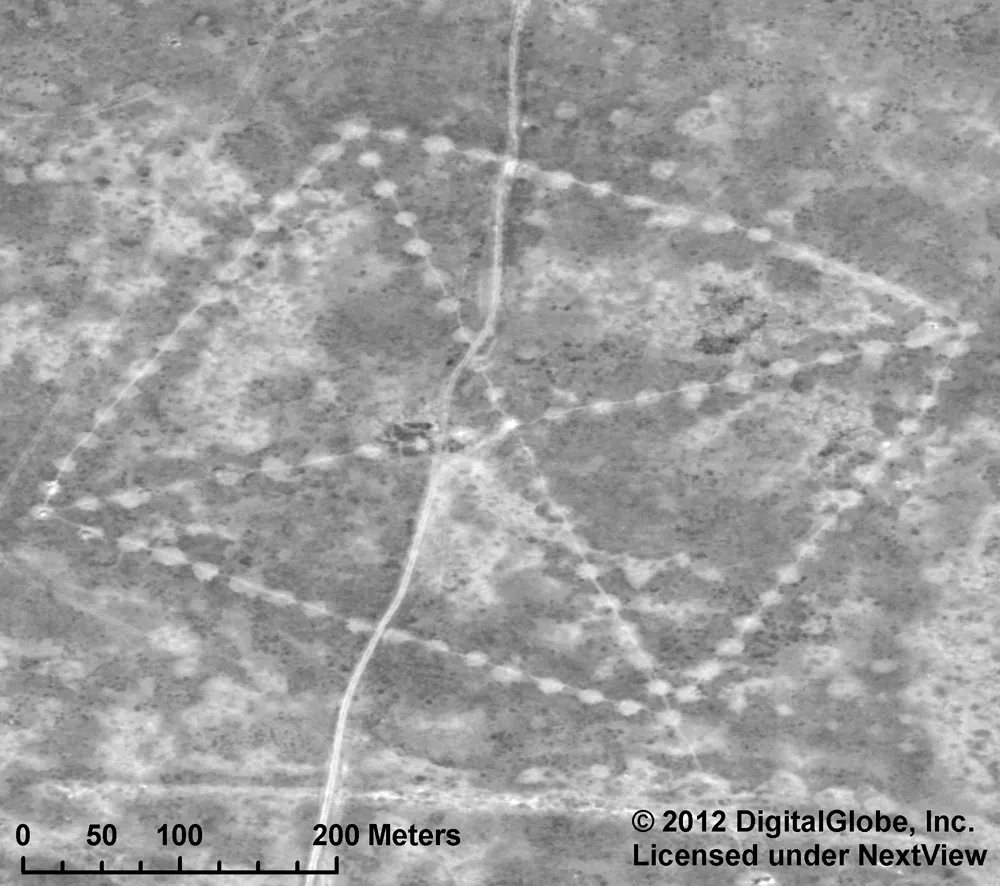

In the vast steppes of northern Kazakhstan, satellite imagery has revealed another mystery: over 260 geometric earthworks, many forming rings, squares, crosses, and swastika-like spirals. These geoglyphs span several kilometers and are invisible at ground level, only satellites and aerial views bring them into focus.

Image credit: NASA.

Often referred to as the Turgai Geoglyphs, they were first noticed in the early 2000s and have since become the subject of archaeological investigation. Radiocarbon dating places some of the structures between 2,000 and 8,000 years old, making them potentially among the oldest large-scale land markings ever discovered.

Their original builders remain unidentified, and no writing or obvious artifacts have been linked to them. Some alignments suggest solar or seasonal functions, but the full cultural and symbolic framework behind these creations is still being pieced together. Like the Nazca and Sajama lines, they were made to be seen from above, long before anyone had the means to do so.

Were they really meant to be seen from above?

This is perhaps the most perplexing aspect of all these ancient geoglyphs: their design only becomes clear when viewed from high altitudes. It’s as if the builders anticipated a perspective they could never reach. That has led to a variety of speculative theories, some scientific, others bordering on the fringe.

One popular hypothesis suggests that the lines were intended for divine or spiritual viewers, gods, ancestors, or sky spirits who would observe human actions from above. Others believe the geoglyphs reflect an early form of astronomical or cosmological mapping, encoding knowledge of the heavens onto the Earth. Still others propose that the elevated perspective was symbolic, meant to convey power or ritual purity, even if it couldn’t be physically accessed.

What unites them all is their stubborn resistance to easy interpretation. The sheer accuracy and scale of the lines, accomplished without aerial tools, continue to challenge our assumptions about what ancient civilizations could plan, organize, and achieve.

What science can — and can’t — explain

Today’s technology has made it easier than ever to spot these ancient markings. With satellite imagery, LIDAR scans, and aerial photography, we can now follow the full sweep of Bolivia’s Sajama Lines, uncover new geoglyphs in Kazakhstan, and trace even the faintest shapes in Peru’s desert. The lines are clearer than ever. But their meaning still slips through our fingers.

Researchers have learned a lot about how these geoglyphs were made. The Nazca people, for example, used nothing more than wooden stakes and simple tools to plot out enormous shapes with remarkable precision. In Bolivia, erosion patterns help date the lines that crisscross the high plains. We know more about the methods, the materials, and the timelines, but not much more about the “why.”

Strangely, the clearer the picture becomes, the harder it is to explain. Patterns grow more tangled, regional styles blur together, and the deeper logic behind them stays just out of reach. Science can show us where and how these lines were made. Understanding what they meant, and to whom, is a different challenge entirely.