There’s a sunken structure older than the pyramids resting beneath the sea off Israel’s coast — part of a 9,000-year-old village known as Atlit Yam.

Submerged in shallow water just a few hundred meters from the shoreline, Atlit Yam remained hidden for thousands of years. It wasn’t swallowed by sand or jungle, but by the sea itself, it was actually the result of a sudden and catastrophic event in the distant past. You might even call it the Atlantis of the Middle East.

What has been uncovered since its discovery has challenged long-held assumptions about the timeline of civilization, agriculture, engineering, and how early humans lived together in permanent communities.

Atlit Yam is not just older than the pyramids. It’s older than writing, wheels, and metallurgy. And yet it shows signs of sophisticated planning, water management, and even ceremonial architecture. Despite all this, no one can say for sure who built it, what they believed, or why they vanished so suddenly.

How a sunken structure older than the pyramids was preserved beneath the sea

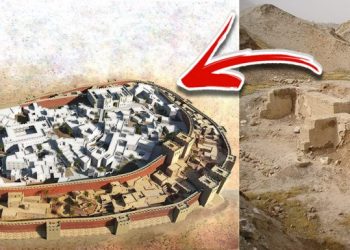

The site came to light in 1984, when marine archaeologist Ehud Galili was conducting a routine survey of the seabed near the modern Israeli town of Atlit. What first appeared to be random stone formations turned out to be the remains of a large, carefully organized Neolithic settlement. Today, Atlit Yam lies about ten meters underwater, spread across more than 40,000 square meters.

Radiocarbon dating places the site between 6900 and 6300 BCE, making it thousands of years older than Egypt’s earliest monumental architecture. Excavations have revealed rectangular stone houses with plastered floors, open courtyards, hearths, storage pits, and even an elaborate freshwater well dug directly into the coastal aquifer. Surrounding the village are tools, fishing gear, animal bones, and remnants of grain, suggesting a population that relied on a mix of farming and fishing.

The reason Atlit Yam is so well-preserved has everything to do with the water. The sea didn’t erode it. It protected it. Like many other sites across the world. The mud and silt created a perfect seal, preserving not just stonework but fragile organic materials as well. The sunken structure older than the pyramids is one of the best-preserved prehistoric coastal sites in the world precisely because of its sudden submersion.

The stone circle at the heart of the mystery

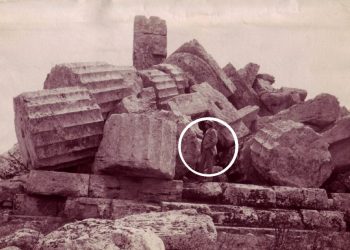

When I said structure, this is what I was mainly referring to.

Near the center of Atlit Yam, archaeologists uncovered a semicircle of seven massive stones, each one standing upright around what was once a spring. They are not scattered or toppled. They were placed with care, each upright block locked into position nearly 9,000 years ago.

Some of them weigh several tons. And yet they were moved, raised, and aligned by hand, without the help of wheels or metal tools. Their surfaces are smooth in places, but not untouched. Shallow basins have been carved into the tops of some, subtle recesses that hint at purpose. Perhaps they once held water. Perhaps something else.

No one knows for certain why the stones were arranged this way. The arc they form is too precise to be accidental. Some researchers suggest they may have served as a gathering place, a site for shared rituals or seasonal ceremonies tied to water. Others believe the alignment might be more than symbolic. A few have proposed that the stones were positioned in relation to the movement of the Sun or stars. I believe the latter.

Their arrangement invites comparison to other megalithic sites like Stonehenge, but this one is older by thousands of years. If the people of Atlit Yam were observing the sky and measuring time through stone, it would place the beginnings of astronomy far earlier than most histories allow. And I concur.

What is peculiar is that there are no carvings here. There are no calendars. There are no visible signs to confirm the theory. What remains is the weight of the stones, their deliberate placement, and the quiet sense that they once meant something more. Nothing has been proven. But to stand in front of them, even underwater, is to feel the pull of a question we have not yet learned how to ask.

Burials, disease, and sudden destruction

Among the site’s most poignant discoveries are its graves. Archaeologists found several human burials within the village, including one especially intimate example: a woman and child interred together, their bodies laid out with care and respect. The grave offers a rare look at social bonds and burial customs from a time before writing.

Scientific analysis revealed the woman had suffered from tuberculosis, making her remains one of the earliest known cases of the disease in the archaeological record. This pushed the origin of tuberculosis thousands of years earlier than previously believed.

But while individual deaths are expected in any community, the end of Atlit Yam itself was anything but ordinary. The entire site appears to have been abandoned all at once, with no evidence of warfare, famine, or prolonged decay. The leading theory is that a massive tsunami — triggered by a volcanic collapse on Mount Etna in Sicily — swept across the eastern Mediterranean and drowned the entire village. Geological deposits along the coast support this theory.

A disaster of that scale would have been sudden and devastating. The people of Atlit Yam likely had no time to flee. Their homes, belongings, and lives were simply engulfed.

A glimpse into the lives that once moved through these walls

Nothing about Atlit Yam feels accidental. The layout of its homes, the channels that once carried water, the central well — they all speak to people who understood how to live in one place, and how to live together. This was a community with structure. Not just in the stones, but in the way they approached survival.

They farmed the land, harvested the sea, and buried their dead with care. They planned where to place their homes and how to access freshwater. That kind of order doesn’t appear without conversation, cooperation, and shared memory.

What they left behind may be even more telling. Among the artifacts found at the site are tools made from obsidian, a volcanic glass that doesn’t occur naturally along the Israeli coast. The closest known sources lie in modern-day Turkey, hundreds of kilometers to the north. That kind of material doesn’t drift in with the tide. It has to be carried, traded, passed hand to hand. Whatever their route, the people of Atlit Yam had ties that reached beyond the shoreline.

Atlit Yam was a functioning settlement. The layout of the homes, the location of the well, the presence of storage areas and work spaces — all of it points to people who understood how to live in one place for a long time. Nothing about the site suggests a seasonal camp.

They worked with the land, made use of the sea, and organized their space with purpose. Then the sea changed, and their world disappeared.

The people behind Atlit Yam have no name

Atlit Yam offers no names, no written words, no symbols we can follow. The people who built this place left behind walls, wells, and stone tools, but not their voice. No inscription marks who they were, where they came from, or how they saw the world around them.

Some archaeologists suggest the site was part of a larger Neolithic tradition that once stretched across the Levant. Others believe it may have belonged to a distinct coastal culture, shaped by the shoreline and the sea. There are theories, but no certainty. What remains is a site without a signature.

Much of it is still buried beneath layers of silt. What has been uncovered is only a fragment. Working underwater is slow. The tides shift, sand drifts, and every excavation demands patience and care. It may take years before the rest of Atlit Yam comes into view, if it ever does. Whatever answers remain are still underwater.

What the site does show, even in its silence, is a community that had settled into a way of life. The homes were carefully built. The dead were buried with intention. The well was dug deep, and the carved stones placed around the spring suggest that meaning, not just survival, shaped this place.

There is no gold at Atlit Yam. No mythic ruins or towering monuments. What survives is something quieter. A village that stayed intact because it vanished all at once, pulled beneath the sea in a single, irreversible moment. The memory of its people wasn’t passed down. It was preserved by accident.

Now, as archaeologists work to recover its outline, stone by stone, we’re left to imagine what was lost. These people were watching the skies, digging wells, growing food, and burying their dead before the pyramids were even a thought. They are not mentioned in any history, but their presence remains, just below the surface.

The sea covered their world, but it did not erase it. And in that silence, we begin to hear their story.