Across the ancient world, people told stories of the gods who descended from the stars and brought order, time, and knowledge to the Earth.

Who were the gods who descended from the stars?

In the heat of the Mesopotamian summer, workers brushed dust from a clay tablet buried beneath centuries of soil. The script was Sumerian, cuneiform, etched with purpose. Its lines spoke of kingship descending from the heavens, of gods who once walked the Earth and returned to the stars. These were not abstract symbols. To the people who carved them, the gods descended from the stars, and that descent shaped the birth of civilization.

This idea did not belong to Mesopotamia alone. On cliffs in West Africa, in temples across Central America, and in the highlands of the Andes, stories emerged of beings who came from the sky. They arrived not as mythic metaphors but as presences remembered in detail; often with names, tasks, and destinations. These stories may not be evidence of any alien contact, but they are unmistakable in pattern. Across continents and centuries, early peoples believed that the origin of their knowledge, their order, and their identity came from above.

The Anunnaki and the memory of divine rule

The earliest written literature emerged in Sumer (based on current evidence), in what is now southern Iraq. Its tablets record a world where deities were not distant concepts. They were rulers, architects, and enforcers. Among them were the so-called Anunnaki, a group of divine beings associated with the heavens, the underworld, and the fate of humankind.

In the Eridu Genesis and the Epic of Atrahasis, the Anunnaki are described as descending from the sky to organize the Earth. They assign duties to other gods, create humans to serve them, and later bring floods to reset the balance. Kingship itself is said to have been “lowered from heaven,” a phrase repeated in different contexts and cities. In this worldview, governance began not with human invention, but with a celestial mandate.

As Mesopotamian society evolved, so did the roles of the Anunnaki. Some remained creators. Others, like Enlil and Enki, took on judicial and cosmic functions. These gods were not static icons. They acted, traveled, and judged. And while modern scholars interpret these accounts through a mythological lens, the language of descent, from above to below, then back again, is consistent. To early Mesopotamians, the gods descended from the stars and brought order with them. But stories of “celestial” beings are not tied only to Mesopotamia. If we research a bit more, we find that such stories are very common across the world.

The Dogon and the silent star

In the sandstone ridges of Mali’s Bandiagara Escarpment, the Dogon people preserved an oral tradition built on observation, ritual, and an enduring relationship with the sky. At the center of their cosmology stands Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky. But it is not alone.

According to reports by French ethnographers in the mid-20th century, Dogon priests described Sirius as part of a system with an invisible companion — small, heavy, and moving in a defined orbit. They also spoke of its importance in cosmic balance. These accounts, published by Marcel Griaule and Germaine Dieterlen, have been cited as evidence of unexpected astronomical knowledge.

Today, modern astronomy identifies this object as Sirius B, a white dwarf first observed in the 19th century. Whether the Dogon understanding predates European contact remains a subject of debate. Later researchers questioned the accuracy of Griaule’s findings, suggesting that key details may have been introduced during earlier interactions. Still, within Dogon cosmology, the idea of descent from the stars remains foundational.

The Dogon speak of the Nommo, amphibious beings said to have come from the Sirius system to bring structure to the world. According to tradition, they arrived, introduced language and order, and returned to the stars. Their story is embedded in Dogon identity, reflected in ceremonial masks, agricultural rites, and annual festivals.

French anthropologists Marcel Griaule and Germaine Dieterlen documented these accounts during fieldwork in the 1930s and 1940s. Their findings, published in European journals, attracted global attention for their detail and apparent astronomical insight. Some researchers later argued that Dogon knowledge of Sirius B may have been influenced by earlier exposure to Western science. Others maintain that the tradition’s symbolic depth suggests a longer, independent origin.

While the question of source remains debated, the Dogon cosmology reflects an enduring belief: the gods descended from the stars and left a pattern in the sky worth remembering. In their rituals, the heavens are not abstract. They are ancestral. But wait, there’s more.

Mesoamerica and the return of the Feathered Serpent

In the heart of ancient Mesoamerica, from the pyramids of Teotihuacan to the rainforests of the Yucatán, civilizations tracked the stars with remarkable precision. Their gods were not only linked to celestial bodies, they were believed to come from them.

Among the Aztec and Maya, one of the most enduring figures is Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent. He was said to have arrived from the east, bringing maize, astronomy, and ceremonial law. His movements across the sky were associated with the planet Venus, which the Maya charted with astonishing detail.

Descriptions of Quetzalcoatl’s departure vary. In some accounts, he crossed the sea. In others, he returned to the sky. The cycle of his disappearance and promised return mirrored Venus itself, which vanished from view and later reappeared as a morning or evening star. His presence marked the passage of time. His absence shaped expectation.

The Popol Vuh, the creation story of the K’iche’ Maya, speaks of gods and ancestors who descended from the sky to shape the Earth. These figures were active. They established calendars, defined rituals, and left tools and stories behind. They were not imagined in abstraction. They were described as teachers, travelers, and builders.

In the highlands of Peru and Bolivia, Viracocha played a similar role. He emerged from Lake Titicaca, instructed the people, then disappeared toward the horizon. Though not explicitly called a sky-being, his solar and stellar associations remain clear. His appearance was linked to cultural transformation.

Across the Americas, the belief that gods descended from the stars shaped how people measured time, conducted rituals, and remembered where knowledge came from.

Reading descent through the stars

When early civilizations said their gods came from the stars, they may have been describing more than spiritual myth. Across cultures, celestial events shaped the rhythm of life. A god’s arrival could reflect the heliacal rising of a bright star. A descent might follow the arc of a meteor shower. In many traditions, constellations were understood as beings with stories, movements, and intent.

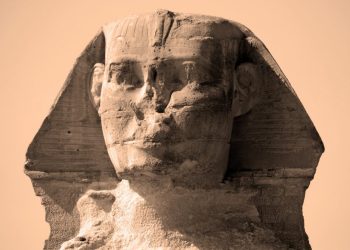

The Egyptians timed the flooding of the Nile with the first reappearance of Sirius in the dawn sky. In Australia, Aboriginal Dreamtime stories describe ancestral figures who crossed the heavens and shaped the Earth below. In Polynesia, navigators told origin stories tied to specific star clusters, which they followed across thousands of kilometers of open ocean.

These connections were not symbolic alone. The stars offered consistency. Through observation and memory, people built systems that depended on their timing. The descent of gods, in many traditions, reflected not just belief, but the return of light at the right time.

Authority born from above

In nearly every early society, the most essential structures — kingship, agriculture, law — were described as coming from the sky. This was not metaphor. It was origin. Rulers traced their lineage to celestial figures. Ritual calendars were aligned with the stars. Sowing and harvesting followed their motion.

In Sumer, records describe kingship being lowered from heaven. In Egypt, rulers joined the constellation of Orion after death. In China, the Mandate of Heaven determined whether dynasties rose or fell. In Mesoamerica, elite families claimed descent from sky-beings who arrived to teach and organize.

This structure was not built only for control. It created meaning. The stars offered reference points that persisted beyond the span of a lifetime. They explained regularity. They gave structure to power. Order came not from invention, but from alignment with what was already above.

Looking upward with the same question

The belief that gods descended from the stars lasted because it was tied to observation. People saw consistent movements above and connected them to patterns in their own lives. The stars were not distant. They were present, structured, and visible. Their return marked seasons, guided planting, and aligned with festivals. From that consistency, stories formed.

These accounts did not emerge from confusion. They were shaped by measurement, refined through practice, and passed along in ceremonies and ritual calendars. Whether the stories describe events or encode timing, they helped early societies track what mattered.

Today, we search the sky with satellites and telescopes. We catalog stars and measure orbits. But the act of looking up has not changed. The methods are different. The question is the same.