The Great Library of Alexandra is without a doubt one of the most famous libraries of the ancient world.

The Great Library of Alexandria was ancient history’s most ambitious attempt to gather all known human knowledge in one place. From scientific breakthroughs to poetic masterpieces, it held hundreds of thousands of scrolls—until centuries of war and political upheaval erased it from existence. These 30 facts reveal the scope of its vision, the brilliance of its scholars, and the mystery behind its fall.

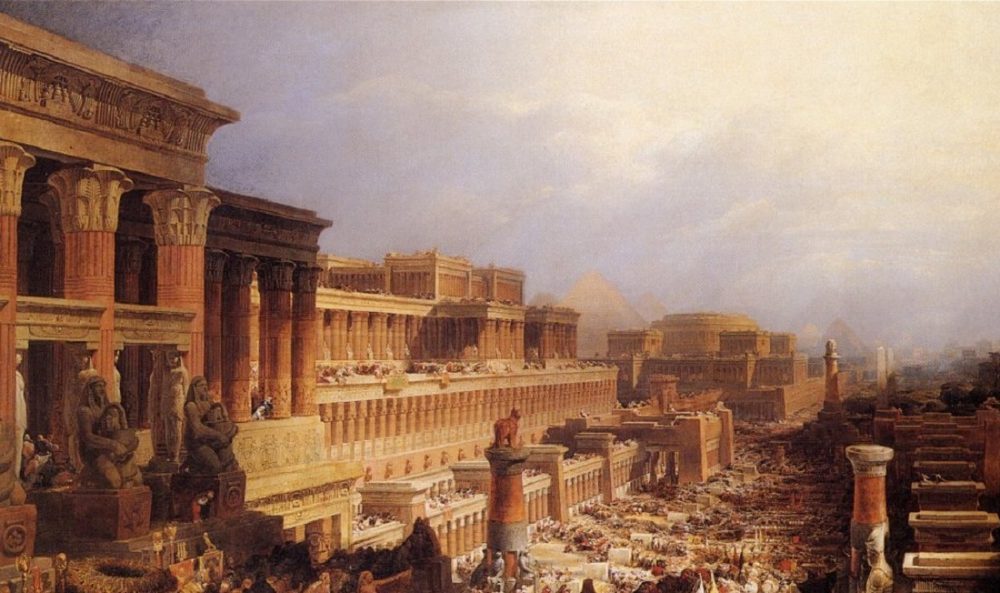

The Great Library of Alexandria

1. The library was born from exile. The idea of the Great Library of Alexandria came from Demetrius of Phalerum, a former Athenian statesman exiled to Egypt. A student of Aristotle, he envisioned a place that could house all human knowledge—an idea embraced by the new ruling dynasty.

2. Its creation began under Ptolemy I. Although it likely flourished under Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the groundwork was laid by his father, Ptolemy I Soter, one of Alexander the Great’s generals and the founder of the Ptolemaic dynasty.

3. It wasn’t just a library—it was a research institute. The library was part of the Mouseion, an academic and cultural complex dedicated to the nine Muses, much like a university or think tank.

4. The Musaeum was modeled after Aristotle’s school. Its design echoed Aristotle’s Lyceum, with gardens, lecture halls, dining areas, and collections meant to nurture scholarly life.

5. No one knows exactly what it looked like. Despite its fame, the exact layout of the Great Library of Alexandria remains a mystery, as no architectural plans or physical remains have survived.

A mission to collect the world’s knowledge

6. The goal was total knowledge acquisition. The Ptolemies sought to obtain every known written work—scrolls, books, treatises—from across Egypt, Greece, Persia, India, and beyond.

7. Books were seized from incoming ships. Ships docking at Alexandria were inspected for scrolls. Originals were taken, copied by scribes, and often kept—while copies were returned.

8. It may have held up to 700,000 scrolls. Estimates range from 400,000 to 700,000 documents at its peak—covering philosophy, science, medicine, astronomy, and literature.

9. Scrolls were stored in multiple buildings. Some scholars believe that overflow collections were housed in a second library within the Serapeum, a temple to the Greco-Egyptian god Serapis.

10. It preserved texts from lost civilizations. Many works from Mesopotamia, Egypt, and India may have survived thanks to translations and copies stored in the library.

A haven for ancient scholars

11. Zenodotus was its first known librarian. A literary scholar and editor of Homer, Zenodotus of Ephesus is credited with organizing the scrolls and developing early cataloging systems.

12. Eratosthenes calculated the Earth’s size. Working at the library, Eratosthenes of Cyrene used shadows and geometry to estimate the Earth’s circumference with surprising accuracy.

13. Apollonius of Rhodes wrote the Argonautica. This epic poem, based on the journey of Jason and the Argonauts, was composed by the library’s second head librarian.

14. Aristarchus proposed a heliocentric model. Centuries before Copernicus, Aristarchus of Samos suggested that the Earth orbits the Sun—a radical idea preserved in Alexandria.

15. It was a center for grammatical science. cholars like Aristophanes of Byzantium and Aristarchus of Samothrace developed the foundations of grammar and textual criticism.

Myths, destruction, and decline

16. The destruction wasn’t a single event. Contrary to popular belief, the Great Library of Alexandria did not burn down in a single catastrophe—it declined over centuries.

17. Intellectual purges weakened it early. In 145 BC, Ptolemy VIII Physcon expelled many scholars from Alexandria, marking the beginning of its intellectual decline.

18. Julius Caesar may have burned part of it. In 48 BC, Caesar set fire to ships in Alexandria’s harbor during a civil war. The flames likely spread to scroll storage facilities.

19. The fire’s impact remains uncertain. While some scrolls were lost, many historians believe much of the library survived Caesar’s fire and continued operating.

20. It may have been destroyed during Roman battles. In 272 AD, during Emperor Aurelian’s battle to retake Alexandria, large parts of the royal quarter—including the library—were destroyed.

21. Diocletian’s siege finished the job. If any part of the library remained after Aurelian’s campaign, it may have been lost forever during Diocletian’s siege in 297 AD.

22. Christianity changed scholarly priorities. As the Roman Empire adopted Christianity, secular scholarship lost prestige and funding, hastening the library’s final disappearance.

23. The Serapeum library was destroyed by a mob. In 391 AD, Christian zealots destroyed the Serapeum—likely wiping out the last remnants of the Alexandrian book collection.

24. We don’t know exactly what was lost. Because many scrolls existed only in that library, we have no catalog of what vanished—just traces and secondhand references.

Legacy, myths, and modern echoes

25. The legend outshines the truth. Over the centuries, the Great Library of Alexandria has become a symbol of lost wisdom, even as facts about it remain limited.

26. It wasn’t the first library. Earlier libraries existed in Mesopotamia, including the Royal Library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh, which housed over 30,000 clay tablets.

27. Writing storage dates to 2500 BC. The curation of written texts began in Sumerian cities like Uruk, where early records of accounting and law were stored on tablets.

28. It influenced how we think about knowledge. The idea of centralizing human knowledge for study inspired modern libraries, research institutes, and even the concept of open science.

29. Its story has fueled centuries of fascination. Writers, historians, and filmmakers have repeatedly returned to the Great Library as a symbol of humanity’s fragile relationship with knowledge.

30. A modern version exists today. In 2002, Egypt opened the Bibliotheca Alexandrina—a futuristic library built near the original site. It stands as a tribute to the ambition of the ancient library and its enduring legacy.