In a night sky full of stars, it’s unsettling to find a place where there seem to be none at all. But that’s exactly what you’ll see if you point a telescope toward a small region of the constellation Ophiuchus. There, like a cosmic blackout, sits Barnard 68 — a dense cloud of dust so thick it blocks the starlight behind it entirely. And while it may look like a hole in space, it’s actually something far stranger.

A dark cloud with no stars behind it

Barnard 68 is what astronomers call a dark absorption nebula, or more specifically, a Bok globule — a tightly packed pocket of interstellar dust and molecular gas. It’s located just 400 light-years from Earth, making it one of the nearest examples of its kind.

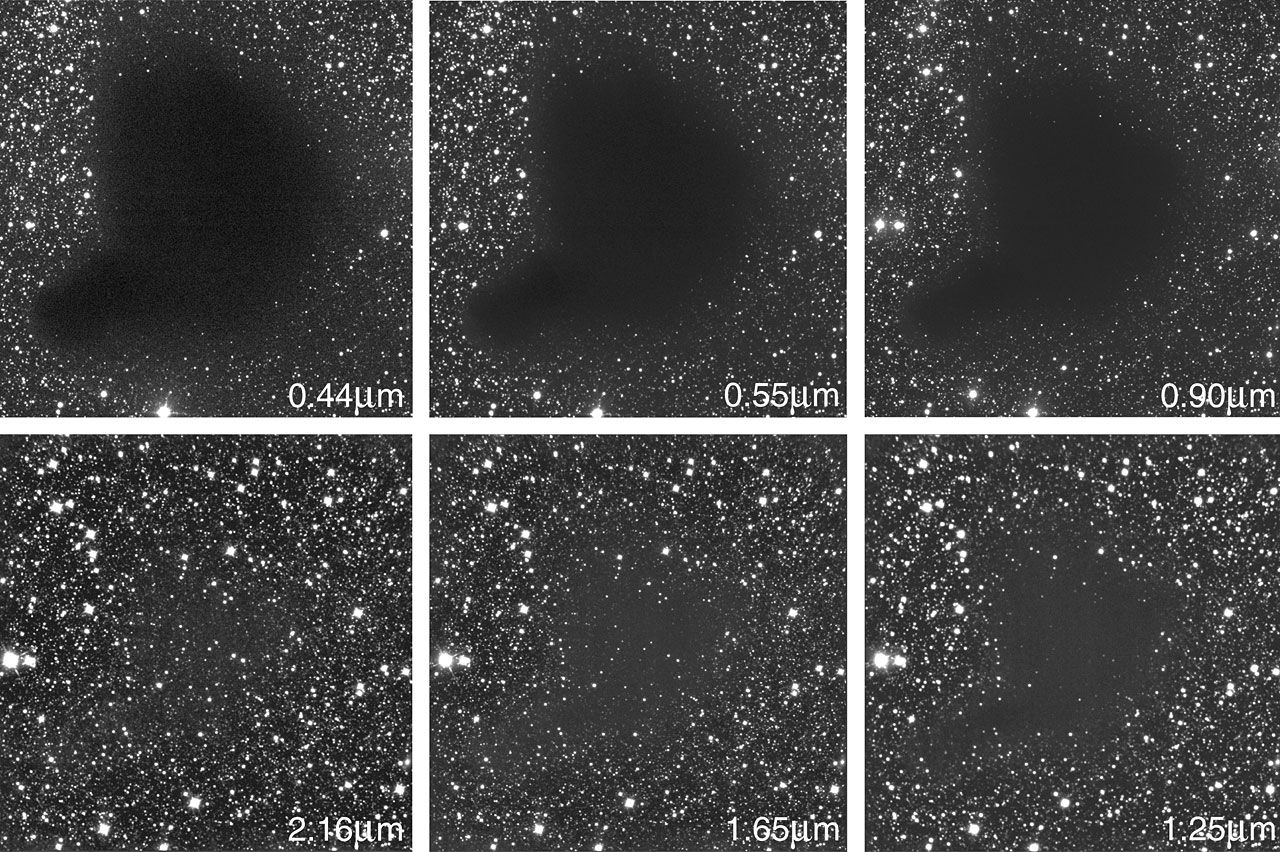

At visible wavelengths, Barnard 68 appears as a perfect void: no stars, no light, no hints of what lies behind. But that darkness isn’t empty space. It’s matter — dense, cold, and light-absorbing.

According to NASA, “What used to be considered a hole in the sky is now known to astronomers as a dark molecular cloud. Here, a high concentration of dust and molecular gas absorbs practically all the visible light emitted from background stars.”

This makes Barnard 68 not just visually eerie, but scientifically unique. It offers astronomers a rare, unobstructed look at the earliest stages of star formation.

Looking into the darkness with infrared light

While Barnard 68 is impenetrable to visible light, it doesn’t stay hidden forever. Using infrared telescopes, scientists have been able to peer through the darkness. Observations by the Very Large Telescope in Chile revealed more than 3,700 background stars — previously blocked by the nebula’s dusty curtain — with about 1,000 clearly visible in infrared wavelengths.

These findings confirmed just how dense the cloud really is. With a mass roughly twice that of our Sun and a diameter of about half a light-year, Barnard 68 is massive, but compact. Its edges are sharply defined — a clue that it’s gravitationally bound and likely in a transitional state.

A star waiting to be born

Barnard 68 isn’t just a passive object. It’s alive, in a way — and its stillness is temporary. Based on its structure and internal conditions, astronomers believe it’s on the verge of collapse. Over the next few hundred thousand years, gravity will likely pull the dust and gas inward until it ignites, forming one or more small stars.

If that happens, this dark nebula will disappear from view — replaced by glowing young stars and surrounded by warm interstellar gas. What looks today like a starless void is, in reality, a stellar nursery, caught in the quiet before birth.

Barnard 68 offers a rare opportunity to study how stars begin — not in bright, explosive events, but in dark, silent clouds, hidden from view. These regions are among the coldest and most isolated environments in the known universe.

What makes Barnard 68 especially compelling is its proximity and clarity. It’s close enough to study in detail, and opaque enough to offer a perfect contrast against the star-filled sky behind it. It reminds us that in space, darkness isn’t always empty — sometimes, it’s just waiting to shine.