What if one of the most iconic vessels in human history wasn’t shaped like a boat at all? An ancient clay tablet reveals the ark was round—closer to a giant floating bowl than the long wooden ship described in later traditions. This 4,000-year-old Babylonian relic doesn’t just reframe the shape of the Ark—it rewrites the entire narrative of how early civilizations recorded engineering, survival, and memory.

A chance encounter with ancient flood blueprints

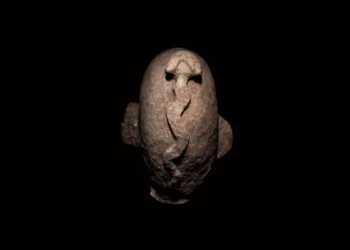

British Museum curator Irving Finkel didn’t expect much when a visitor handed him a palm-sized clay tablet that had been passed down through a family for decades. But what he held turned out to be a one-in-a-million find: a cuneiform tablet dating back to 1750 BCE that contained a detailed flood story—complete with construction plans for a round ark.

This wasn’t just another version of the myth. It was a blueprint.

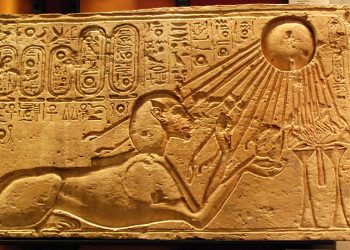

The hero in this story wasn’t Noah but Atra-hasis, a Babylonian figure who receives divine warning from the god Enki. Rather than build a traditional ship, Atra-hasis is instructed to construct a massive circular vessel, waterproofed with bitumen and held together by an immense quantity of rope and wooden ribs.

“Quantities of palm-fiber rope, wooden ribs, and bathfuls of hot bitumen to waterproof the finished vessel… The amount of rope prescribed, stretched out in a line, would reach from London to Edinburgh,” Finkel explained.

This round ark, known as a coracle, was far from symbolic—it was designed to float in floodwaters with stability, not to sail. It’s the kind of vessel you build when your only mission is to survive the storm.

The ark’s true shape and staggering scale

The ancient clay tablet reveals the ark was round, yes—but it was also enormous. According to the cuneiform instructions, the vessel had a surface area of around 2.2 square miles, with towering 20-foot-high walls. Its construction would have required vast amounts of materials, suggesting a highly organized effort—possibly led by temple or palace authorities in Mesopotamia.

The details are practical, not poetic. This wasn’t mythology—it was logistics.

Finkel, who documented the find in his book The Ark Before Noah, emphasized that the story is startling not because it exists, but because of its engineering precision. The tablet gives instructions that could, in theory, be followed today.

“The clay tablet features startling new content,” he wrote. “It’s not just myth. It’s a construction plan.”

Why would the ark be round?

The concept of a circular ark may seem strange—until you consider its function. A coracle is highly stable, especially in turbulent water. Its round shape ensures it won’t tip over easily. In a massive flood, this design makes perfect sense.

Unlike later versions of the Ark meant to preserve animals in pairs and navigate the sea, Atra-hasis’s ark was intended for buoyancy over navigation. It was built to survive, not to travel.

And while the Bible describes a long, rectangular vessel with three decks and a door on its side, this Babylonian account is far older—and offers no symbolic flourishes. It’s all about staying afloat.

A new chapter in an ancient story

This isn’t the only flood narrative from the ancient world. Similar tales appear in the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, the Greek tale of Deucalion and Pyrrha, and numerous indigenous traditions. But the fact that the ancient clay tablet reveals the ark was round—and includes specific materials and measurements—adds a layer of realism to what has long been treated as allegory.

Finkel’s research opens up new avenues of exploration: How many flood myths are based on shared memory? Could regional disasters have inspired global legends? And did ancient people pass down practical survival knowledge wrapped in myth?

By decoding the cuneiform tablet, researchers are starting to see the Ark not just as a religious symbol, but as an ancient artifact of science, engineering, and storytelling.