Although many people know Egypt because of its pyramids–the Great Pyramid especially–this African country is more than just pyramids.

Egypt isn’t even the country that has the most pyramids. Sudan, its neighboring country, has more pyramids, but that’s not something many people know.

Nonetheless, the land of Pharaohs, Pyramids, mummies, papyrus, and golden sands has a LOT to offer.

And it has been doing that for more than a century, as different Egyptologists, archeologists and researchers ventured out to explore what remains hidden beneath the sand.

The stupefying discoveries we made in Egypt turned out to be more than history changers.

They showed us that, unlike popular belief, the ancient Egyptian civilization was a very sophisticated one. We have not been able to crack the secrets of their pyramids, temples, and forgotten cities, despite making our best effort to understand what was hidden in the sand.

The more we explore Egypt, the more we seem to realize what a treasure trove of history this civilization is.

And it isn’t surprising. After all, the ancient Egyptian civilizations can be traced back to a time when history was not even recorded yet.

That’s why in this article, we bring you 5 stupefying discoveries from ancient Egypt that you should know about.

Egypt’s Atlantis

One of the most amazing discoveries in recent history was made in 1999, when French underwater archaeologist Franck Goddio discovered the sunken remnants of ancient Egypt’s Atlantis: the city of Thonis, or as the ancient Greeks called it, Heracleion.

Located not far from Alexandria, the city of Thonis succumbed to mother nature’s power and sank beneath the ocean, taking with it a great deal of ancient Egypt’s history.

The city of Thonis was of great importance in ancient Egypt. It was there where one of the most essential Pharaonic temples stood. It was there where new Pharaohs would go to receive the divine power of Amun, which legitimized their rule over the land and people of ancient Egypt.

It was there where underwater archeologists also discovered the mythical ancient Egyptian baris, a cargo boat that was mentioned by the Greek writer Herodotus more than 2,500 years ago. The boat had never been found and was considered a myth. But underwater explorations of the city revealed dozens of shipwrecks, and among them was the mythical ship Herodotus wrote about.

Recent exploration of Heraclion has yielded more discoveries.

It has been revealed that the researchers have come across the ancient ruins of a Greek temple, as well as numerous shipwrecks filled with treasure.

Thanks to sophisticated scanning devices, the researchers were able to identify a new part of the city’s main temple, which was completely destroyed as the ancient city was devoured by the sea.

A Geological map way ahead of its time

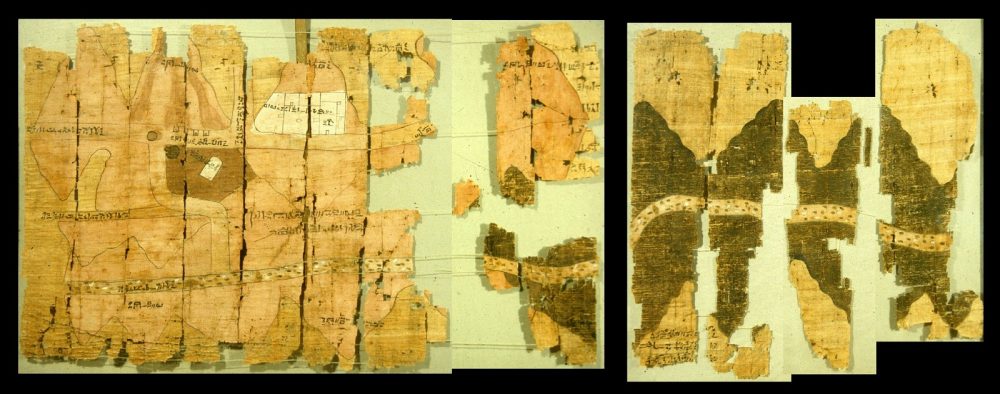

The ancient Egyptians were excellent record keepers. So it isn’t surprising to know that archeologists excavating Egypt’s golden sands came across an antique map. But this map was no ordinary chart. It is considered one of the very first geological maps ever charted on Earth.

The map was drawn on Egyptian papyrus, is believed to be more than 3,000 years old, and is evidence of an incredible ancient Egyptian geological knowledge.

The map was drawn by an official by the name of Amennakhte. And he had the necessary knowledge and skills to draw up an incredible map, now considered the first geological map on Earth and way ahead of its time.

The papyrus–the Turin papyrus map–is believed to have been drawn during the reign of Ramesses IV, sometime during the middle of the 12t century BC. The historical chart was discovered at Deir el-Medina in Thebes, and collected by Bernardino Drovetti (known as Napoleon’s Proconsul) in Egypt sometime before 1824 AD. The map is now kept at the Egyptian Museum, in Turn, Italy.

The map shows a 15-kilometer stretch of Wadi Hammamat and depicts the surrounding hills, the bekhen-stone quarry, and the gold mine and settlement at Bir Umm Fawakhir. In addition to that, the ancient map also includes numerous annotations (written in the hieratic script) identifying the features shown on the map.

Oldest Papyrus of Egypt

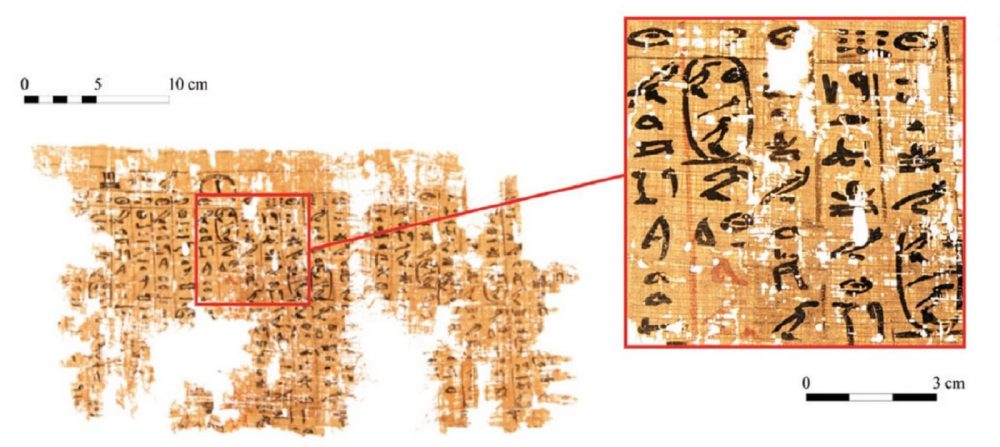

The ancient Egyptians were known for their papyrus-making skills. Eventually, it became a widespread material across the country.

Archeological excavations at the site of Wadi el-Jarf in 2011 revealed an unprecedented discovery. Experts were excavating the ancient harbor located on the shore of the Red Sea, and they discovered hundreds of papyri fragments that date back to the reign of Pharaoh Khufu, the man that commissioned the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Among the papyri fragments, the archeologists discovered an ancient text they later identified as the Journal of Merer.

Merer was an Egyptian that lived 4,500 years ago. He ‘penned down in his journal’ day to day work. When experts translated the ancient text, they found that Mere was an inspector in charge of transporting massive limestones from the quarries at Tura, all the way towards the Giza plateau.

It is believed that Merer and his work crew of sailors were tasked whit transporting massive blocks of limestone that were later used in the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Although the Journal of Merer does not mention that the limestone blocks were specifically used for the construction of the pyramid, given the age of the papyri and their content, experts argue the stones were most likely used in the construction of the pyramid.

The ancient journal does, however, mention “Akhet Khufu as the Great Pyramid, the “Horizon of Khufu.”

4,500-Year-Old Ramp Contraption

To understand why and how the great pyramid of Giza–as well as all other Egyptian pyramids– was built, must be every archaeologist’s dream.

We know that the massive structures were most likely monuments that held the remains of the Pharaohs. We just haven’t found mummies inside the pyramids that suggest so. Also, the three main pyramids of Egypt, those at the Giza plateau, lack their respective mummies, so its a bit difficult to claim the pyramids were tombs.

Nonetheless, understanding how they were built is a fascinating step forward in understanding this ancient civilization.

That’s why an archeological discovery in 2018 was of great importance.

A French archaeological mission was excavating a site called Hatnub, an ancient Egyptian quarry located in Egypt’s Eastern Desert.

There, they discovered what appears to be a contraction that may have been used in ancient times to transport the massive stones up a steep ramp. In other words, they may have discovered a piece of ancient technology that the ancient builders made use of 4,500 years ago when the Pyramid of Khufu was built.

“This system is composed of a central ramp flanked by two staircases with numerous post holes,” Yannis Gourdon, co-director of the joint mission at Hatnub, told Live Science.

“Using a sled which carried a stone block and was attached with ropes to these wooden posts, ancient Egyptians were able to pull up the alabaster blocks out of the quarry on very steep slopes of 20 percent or more.”

Blades made of Meteorites

The ancient Egyptians were very smart. They were curious, and they learned quickly. Evidence of that is that thousands of years ago, even before they understood the use of iron, they made use of iron meteorites.

To understand this, we turn towards Pharaoh Tutankhamun, son of Akhenaten, who ruled over the land of Egypt from 1336 to 1327 BCE. When Howard Carter uncovered King Tut’s tomb in 1925, he obtained priceless artifacts from the undisturbed (until then) ancient tomb. Amid them was a peculiar, unique, iron dagger. But that dagger was not common. This special dagger was built for Egypt’s special king and crafted out of the remnants of a fallen meteorite.

“Beyond the Mediterranean area, the fall of meteorites was perceived as a divine message in other ancient cultures. It is generally accepted that other civilizations around the world, including the Inuit people; the ancient civilizations in Tibet, Syria, and Mesopotamia; and the prehistoric Hopewell people living in Eastern North America from 400 BCE to 400 CE, used meteoritic iron for the production of small tools and ceremonial objects,” wrote scientists in a 2016 study that revealed the nature of the dagger.

Join the discussion and participate in awesome giveaways in our mobile Telegram group. Join Curiosmos on Telegram Today. t.me/Curiosmos