The Eye of the Sahara Atlantis theory suggests that a mysterious circular formation in the African desert may be the ruins of Plato’s legendary lost civilization. Satellite imagery and ancient texts reveal strange parallels—sparking both fascination and fierce debate.

Could Atlantis lie in the heart of the Sahara Desert?

Among the many attempts to locate Plato’s fabled Atlantis, few theories have stirred as much public intrigue as the claim that it lies not beneath the ocean, but beneath the African desert. A growing number of independent researchers now point to a geological formation in Mauritania—known as the Richat Structure or the Eye of the Sahara—as the possible remains of this ancient lost civilization.

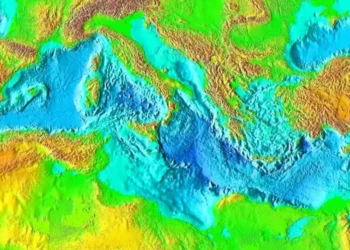

Located in northwestern Africa, the Richat Structure is a massive, circular feature visible from space. Spanning roughly 23 kilometers in diameter, its unusual rings of sediment and stone have puzzled scientists since their discovery. But to some, this is more than a geological oddity—it may be the key to solving one of history’s most enduring mysteries.

In 360 BC, the Greek philosopher Plato first mentioned Atlantis in his dialogues Timaeus and Critias, describing it as a powerful naval empire that existed 9,000 years before his time. According to Plato, Atlantis was a massive island beyond the Pillars of Hercules—believed to be the Strait of Gibraltar—and boasted a circular capital built with alternating rings of land and water. The civilization was eventually destroyed in a cataclysmic event and “vanished beneath the waves.”

These ancient descriptions have long fascinated scholars and pseudoscientists alike. But in recent years, new tools like Google Earth have enabled modern explorers to revisit Plato’s account with fresh eyes—literally.

YouTuber’s viral theory puts Atlantis in the Sahara

Among the most vocal proponents of the Eye of the Sahara Atlantis theory is a content creator named Jimmy Bright. In a YouTube video that has surpassed two million views, Bright lays out his argument, comparing satellite imagery of the Richat Structure with Plato’s original writings.

According to Bright, the Eye’s 23-kilometer diameter closely matches the measurements Plato described for Atlantis’s capital. Its circular, multi-ringed layout—with alternating layers of sediment and what some believe were once water channels—mirrors the concentric design noted in Critias.

Bright also highlights the terrain surrounding the Richat Structure, which Plato described as a “flat and smooth plain” adjacent to the city. He points to the Sahara Desert as matching that description, and even identifies what he claims are ancient dried-up riverbeds in the region—suggesting the presence of water in a long-lost age.

Further supporting his case, Bright notes the mountainous formations to the north of the Richat site. Plato’s Atlantis, he says, was protected by mountains in the north, aligning yet again with the local geography.

Bright’s theory has resonated with many, especially on YouTube, where creators and commenters alike cite the numerous “coincidences” between Plato’s account and the Eye of the Sahara.

A controversial claim with little academic backing

Even as the theory spreads online, most archaeologists and historians aren’t buying it. In academic circles, Atlantis is still viewed as a fictional allegory—a story Plato crafted to explore ideas about politics, morality, and the rise and fall of civilizations.

Skeptics of the Eye of the Sahara theory say it picks and chooses the parts of Plato’s account that fit, while brushing aside what doesn’t. There’s no solid evidence the Richat Structure was ever underwater or home to an advanced society. According to geologists, it’s a natural formation shaped by erosion and uplift—not the remains of a sunken city.

And yet, the idea won’t go away. Even if the science doesn’t support it, the possibility that something ancient and forgotten might lie beneath the sands keeps people wondering. Maybe it’s not Atlantis—but something about the Eye of the Sahara still stirs curiosity.

Until the mystery is truly put to rest, theories like this will keep sparking interest, blending old texts with modern tools—and keeping alive that age-old question: what if Plato wasn’t just making it up?