A mysterious Sumerian star map etched into clay more than 5,000 years ago may hold one of the earliest eyewitness accounts of a catastrophic asteroid event on Earth.

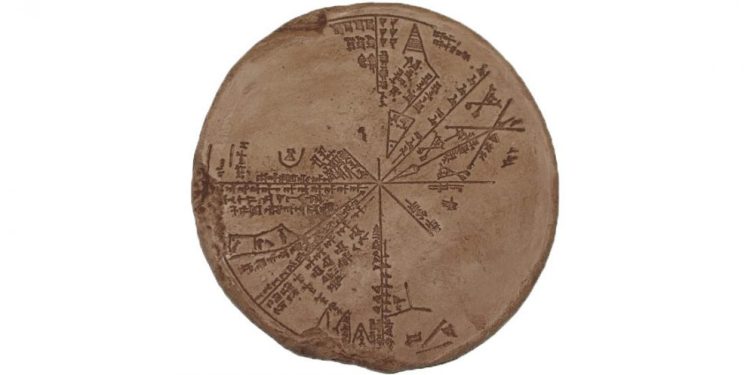

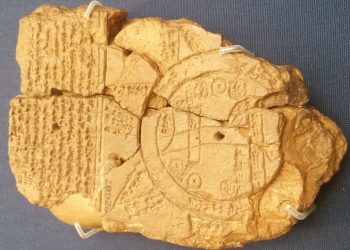

Known as “the Planisphere,” the ancient cuneiform tablet has puzzled historians and astronomers for over a century. It was unearthed in the 19th century during excavations at the ruins of Nineveh in modern-day Iraq, and today it’s housed in the British Museum under the catalog number K8538. For decades, no one could make full sense of it—until modern astronomy software gave researchers a way to reconstruct the night sky as it looked thousands of years ago.

That’s when the clues started lining up.

A cosmic event recorded in clay

The Sumerian star map is believed to be a copy of notes taken by a skilled sky-watcher—an ancient astronomer—who carved his observations onto a clay tablet around 3,123 BCE. The tablet contains celestial data, constellations, and markings of planetary positions. But it also describes something far more dramatic.

In one section, the observer refers to a strange object appearing in the sky—a glowing, fast-moving body he calls a “white stone bowl.” According to researchers, this could be a description of a massive asteroid entering Earth’s atmosphere.

By using astronomical modeling software, scientists were able to align the tablet’s observations with the night sky over Mesopotamia on a specific date: June 29, 3123 BCE.

What they found was staggering: the trajectory described by the Sumerian astronomer appears to match the path of an asteroid believed to have caused the destruction of Köfels in Austria—an event that left no visible crater, but signs of intense geological upheaval.

How a Sumerian star map led to Köfels

Roughly half of the Planisphere tablet is dedicated to charting the position of stars and planets. The other half, however, focuses on an extraordinary event—something so unusual that the observer carefully noted its movement across the sky, relative to known constellations.

Based on these notations, scientists now believe the object was likely an Aten-type asteroid, at least one kilometer wide. These types of asteroids follow orbits that bring them very close to Earth.

What made the Köfels event unusual is the lack of a clear impact crater. But the data from the Sumerian star map may explain why.

According to the analysis, the asteroid entered Earth’s atmosphere at a very low angle—around six degrees. This shallow trajectory likely caused the asteroid to clip a mountaintop—possibly Gamskogel—before disintegrating in the air.

As it tore through the valley near Köfels, the asteroid became a massive fireball approximately five kilometers in diameter, generating extreme pressure that pulverized rock and leveled terrain. But because it was no longer a solid object by the time it hit the surface, no traditional impact crater was left behind.

Ancient knowledge hidden in plain sight

The idea that a Sumerian star map could document such a precise astronomical event thousands of years ago might seem far-fetched—but the evidence is hard to ignore. Researchers found that the tablet’s record of the asteroid’s path was accurate to within one degree of modern calculated trajectories.

In other words, this wasn’t a myth. It was a scientific record—etched by hand in a world without telescopes, satellites, or physics textbooks.

It shows that ancient Sumerians were not just early writers and builders. They were keen observers of the sky, recording cosmic events with enough precision to inform researchers more than five millennia later.