The lost city of Etzanoa may be one of the most remarkable archaeological discoveries in North America — not just because of its size, but because of what it tells us about the people who lived here long before colonization. Located near modern-day Arkansas City, Kansas, this sprawling settlement once housed an estimated 20,000 Native Americans, making it one of the largest known ancient cities on the continent.

For centuries, Etzanoa existed only in legend, like many other ancient cities in the Americas, known from fragmented Spanish accounts and oral history. However, myths often turn into reality, and evidence from archaeological digs rewrites what we thought we knew about early life on the Great Plains.

Rediscovering the lost city of Etzanoa

Archaeologists led by Dr. Donald Blakeslee of Wichita State University uncovered artifacts that confirm the city’s existence. Excavations revealed Spanish horseshoes, iron nails, and a cannonball, likely fired during a 1601 battle between Spanish conquistadors and Indigenous defenders. But the real story is in the soil: signs of planned housing, gardens, and complex infrastructure that suggest an organized, long-lasting civilization.

Blakeslee’s research began with a fresh translation of 17th-century Spanish records, which described a vast city of “many houses” and “abundant people.” These records had long been dismissed, but when cross-referenced with ground-penetrating radar and field excavations, the results lined up almost exactly. The lost city of Etzanoa, it turns out, was no myth.

“What this find represents is totally against what the history books told us. It’s amending history,” said Dr. Blakeslee in 2018.

The lost city of Etzanoa challenges the long-standing assumption that North America was largely empty before European arrival. Historians often portrayed the Great Plains as sparsely populated — but Etzanoa alone may have had more residents than many European cities of the same period.

Artifacts found at the site include stone tools, ceramic fragments, and traded minerals not native to Kansas. These findings suggest that the inhabitants were part of a vast Indigenous trade network, connecting them with other Native groups as far away as the Southwest, the Gulf Coast, and possibly even Central America.

The lost city of Etzanoa and the pattern of forgotten cities

The rediscovery of the lost city of Etzanoa echoes similar breakthroughs across the Americas. In recent years, LIDAR technology — which uses laser pulses to map terrain hidden by jungle or soil — has revealed entire ancient city networks in the Amazon Basin, including wide roads, platforms, reservoirs, and urban layouts. In Honduras, archaeologists uncovered the so-called Lost City of the Monkey God, a sophisticated settlement once buried beneath rainforest canopy.

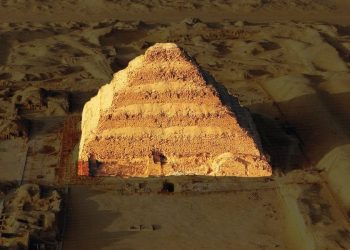

And in North America, cities like Cahokia (near modern St. Louis) are now recognized as massive population centers with pyramids, plazas, and extensive trade. These discoveries point to a powerful truth: the Americas were not an untouched wilderness — they were home to urbanized, complex societies with deep cultural traditions and far-reaching influence.

The lost city of Etzanoa forces us to rethink What We Thought We Knew

The story of the lost city of Etzanoa encourages a closer look at how Indigenous societies in North America lived — and how much we’ve overlooked. Its scale, organization, and longevity point to a complex way of life that doesn’t always appear in the traditional narratives of pre-colonial history. Rather than revising maps or rewriting everything we know, Etzanoa simply adds to a growing body of evidence that Native communities built cities, maintained trade networks, and shaped the land in ways that were every bit as meaningful and sophisticated as their counterparts elsewhere in the world.

But, like many experts have said in the past, there is much more to the Americas than what we have been taught in school. And this leads us to a very important question.

What Else Might Still Be Out There?

Etzanoa may not be the only city of its kind. As new technologies like LIDAR and better archaeological methods become more accessible, researchers are revisiting older texts, oral histories, and overlooked sites — and they’re starting to connect dots that had long been dismissed.

Much of this work is still in its early stages. But if Etzanoa teaches us anything, it’s that the past isn’t fixed. What we know today is just a small part of a much larger story still waiting to be uncovered.