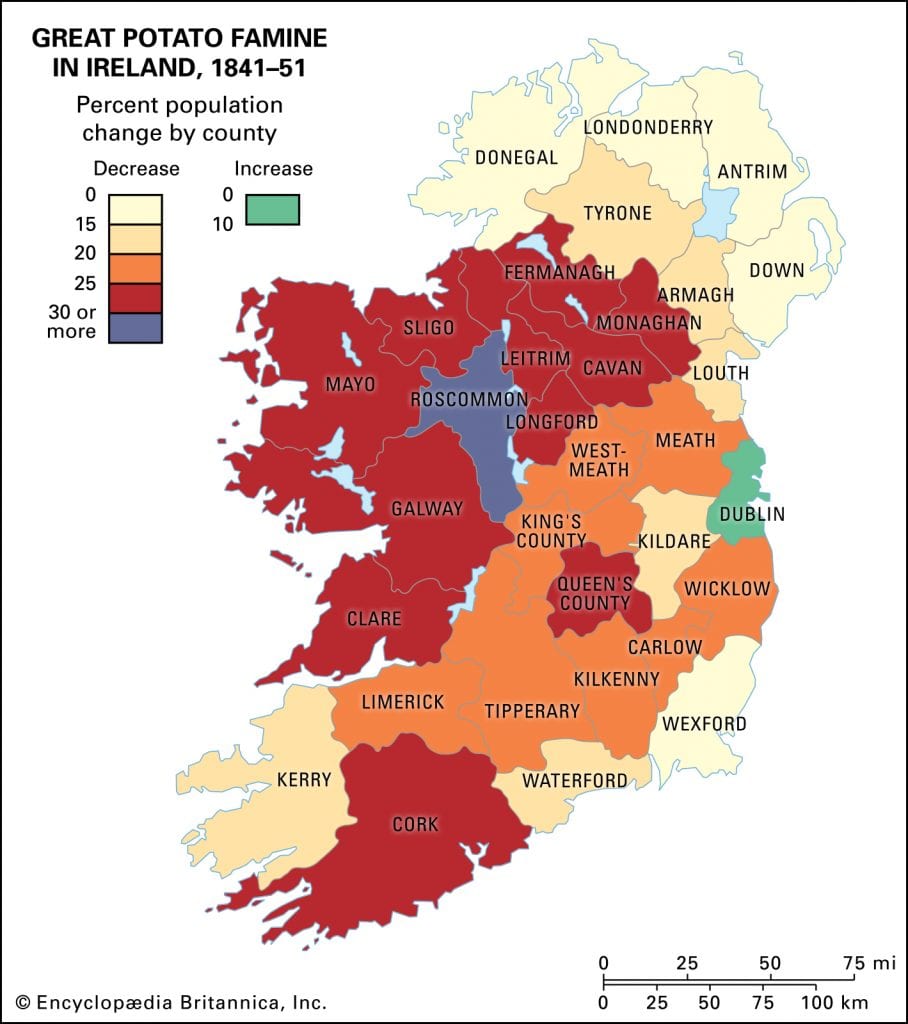

In the middle of the 19th century, one of the most tragic events in the entire history of the country happened in Ireland – a potato blight that led to a terrible famine. During the period from 1845 to 1849, about a quarter of the population died. Echoes of those years are still reflected in modern Irish life. What were the reasons for these events, and why do the descendants of the survivors still hate the British?

Ireland is a beautiful northern country with unique climatic conditions. Cool summers and relatively warm winters, as well as frequent rains, allow local vegetation to turn green all year round. For this reason, the country is also often called Emerald Isle.

In the middle of the 19th century, the Irish began to leave their homes en masse. Their goal was more prosperous states at that time – the United States, Britain. The reason for this outcome was a massive famine, which became possible as a result of the agrarian crisis, the policy of the British authorities, and the outbreak of a potato blight epidemic.

The potato appeared in Ireland after 1590. Giving very bountiful harvests, it quickly became not only a well-appreciated fodder source but also a staple food for local residents. The unpretentious culture made it possible to obtain impressive yields even on a small area of infertile soil.

However, the outbreak of an epidemic caused by the late potato blight fungus in the 1840s began to destroy Irish potatoes at a catastrophic speed, which at that time was practically the only source of food for land tenants. How did it happen that as a result of the shortage of just one agricultural crop, the country lost at that time, according to various estimates, from a quarter to a third of its population?

Potato Blight, Great Famine, and British ill-will

The colonization of the Irish lands by England began in the 12th century. The English nobility confidently took the land plots of local families. Rebellions that broke out from time to time were brutally suppressed. One of the notorious events is the invasion of Oliver Cromwell, whose army staged a real massacre in the besieged city of Drogheda.

By the beginning of the 19th century, Ireland nevertheless became part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. But in relation to the locals, the rather unfair and tough colonial policy continued. The English landlords had rights to almost the entire fertile territory of the green island. Land plots were leased to local people engaged in agriculture. However, the cost of rent was so high that it was the main cause of poverty among the Irish.

The beginning of the Great Famine in the country coincided with the decision of the English nobility to retrain agriculture. It was decided to increase the pasture land at the expense of small land leases. The first potato crop failure occurred in 1845. Tubers infected with phytophthora rotted directly in the ground or storage facilities. The infection spread en masse over the land by streams of water.

At first, this phenomenon did not cause much excitement. Initially, the government tried to support the poor, but most of the aid was expressed in the provision of almost slave conditions in workhouses, where the peasants were forced to work for meager food and a roof over their heads.

In subsequent years, the deplorable situation only worsened. Crop failures and unusually cold winters led to higher land rents. As a result, most of the Irish farmers were literally deprived of their already meager arable land. Fleeing from starvation, many made decisions to leave their homes in search of new homes and new opportunities.

The long journey across the Atlantic was not easy for the poor. Exhausted people in unsanitary conditions traveled for weeks to the shores of America on ships, often no longer suitable for use. Many did not survive travel, dying on the path to a better life.

To top the troubles that befell the country in lean years, real epidemics of typhoid, dysentery, and scurvy began in Ireland. And in 1849, raging cholera claimed about 36,000 lives. In other words, Ireland was devastated by not only the potato blight epidemic but by other illnesses too.

As the situation worsened, the British authorities stopped taking any steps to support the population. British landlords refused to cut rents, and few provided any assistance to their former tenants.

The hard times of the Great Famine ended in 1850 when a full crop of uninfected potatoes was harvested which pretty much gives us the approximate time the potato blight was at its end. The authorities finally made concessions to local residents, canceling the arrears for that period.

Ireland today is a very successful European state. However, the consequences of the Great Famine of the mid-19th century still sound like a pain in the hearts of the descendants of land tenants.

To this day, the population of the country is 2 times smaller than before these events. Relations with the British can still be classified as cold and irreconcilable. The long-standing enmity between peoples, even a century later, does not allow them to forget and forgive the crimes caused by human callousness and greed for the colonial and enslaved population.

Join the discussion and participate in awesome giveaways in our mobile Telegram group. Join Curiosmos on Telegram Today. t.me/Curiosmos

Sources:

• Brandslet, S., & Article from Gemini, N. (2016, June 11). The potato disease that changed the world. Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://partner.sciencenorway.no/forskningno-natural-history-norway/the-potato-disease-that-changed-the-world/1434437

• The Irish Potato Famine and the Birth of Plant Pathology. (n.d.). Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/apsnetfeatures/Pages/PotatoLateBlightPlantDiseasesComponents.aspx

• Great Famine. (n.d.). Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/event/Great-Famine-Irish-history

• History.com Editors. (2017, October 17). Irish Potato Famine. Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://www.history.com/topics/immigration/irish-potato-famine

• Martin, M., Vieira, F., Ho, S., Wales, N., Schubert, M., Seguin-Orlando, A., . . . Gilbert, M. (2015, November 17). Genomic Characterization of a South American Phytophthora Hybrid Mandates Reassessment of the Geographic Origins of Phytophthora infestans. Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://academic.oup.com/mbe/article/33/2/478/2579558