In the late 1960s and early 1970s, NASA went through its golden age. Robotic devices were sent to nearby planets and men were flying to the Moon!

The agency had big ambitions for Mars and plans to run the Voyager program (not to be confused with the research program of the same name that continues its travels in deep space).

The Martian Voyager program was planned to use the powerful Saturn 5 rockets. But at the time, people kept complaining that NASA was spending too much money, and amid many calls for spending cuts, the agency’s budget was slashed and the Voyager program was forgotten.

Instead, a slightly more modest Viking program was initiated, which planned to send two complexes of orbital and landing vehicles with Titan IIIE rockets.

After several years of development, NASA successfully launched Viking 1 on August 20, 1975, and Viking 2 on September 9 of that year. The Viking 1 orbital complex entered orbit around Mars on June 19, and the Viking 2 orbit on August 7, 1976.

Viking 1 was originally scheduled to land on Mars on July 4, 1976. The date was not chosen by chance – then, the US was supposed to celebrate two centuries since the founding of their country.

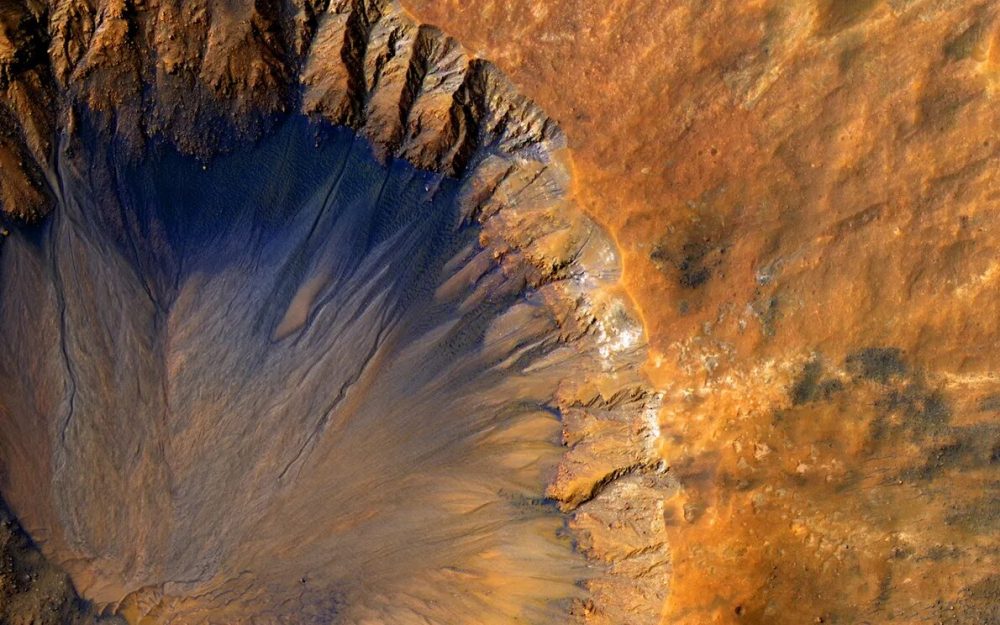

However, when the first images from the Viking 1 orbital probe arrived after June 19, the mission leaders realized that the landing area was too steep and the risks to the lander were great. Therefore, they unanimously decided to postpone the landing until they find a more suitable place.

On July 12, the new landing site was chosen – at a distance of 575 kilometers from the originally planned, but still in the region of the Golden Plain. It was decided to separate the landing section from the orbital one and make a landing on July 20 (which coincides with the celebration of 7 years since the first manned landing on the moon).

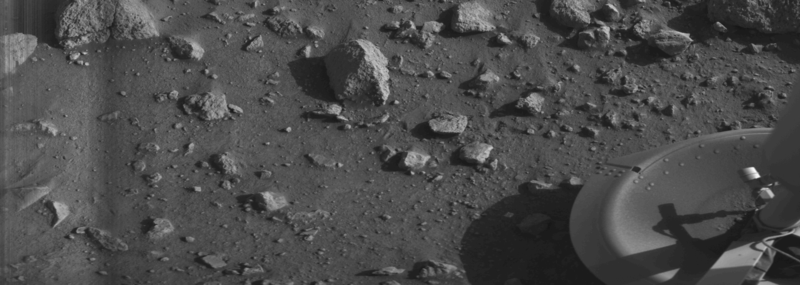

Shortly after landing, Viking 1 uploaded its first photo which you can see below.

The photo clearly shows one of the feet of “Viking 1”, located firmly on the surface – an important thing that every leader of each landing mission wants to notice. But in addition to its engineering value, the photograph had both scientific and historical significance.

This was the first image obtained from the surface of Mars! Probably a disappointment for some of the scientists – only sand and rocks can be seen on it. No trace of any multicellular organisms, as Viking 1 confirmed – if there is life on Mars, it is most likely unicellular.

The real surprises from the mission arrived a few days later.

One of Viking 1’s experiments was called Labeled Release (LR). In short, it can be described as follows: a nutrient medium containing a radioactive isotope is introduced into the soil of Mars. If there are microorganisms in it, they are expected to metabolize food and release radioactive gas.

Both the Viking 1 experiment and the later Viking 2 experiment reported the presence of radioactive gas, and so the team of scientists concluded that there was life on Mars!

But the results of another experiment were disappointing. In this experiment, soil samples were taken, heated to 500 degrees Celsius, and the resulting gases were studied with a Gas Chromatograph – Mass Spectrometer (GCMS).

The experiment showed that there is no significant amount of organic matter in the soil of Mars. The only organic substances that have been confirmed are chloromethane and dichloromethane, and they are considered to have come in secondarily from Earth.

In fact, according to the results of this experiment, the soil on Mars is more lifeless and contains less carbon than the sterile lunar soils delivered to Earth by astronauts from the Apollo program.

So, the question has been asked countless times and is still on the agenda: is there life on Mars?

The final statement adopted by NASA in the 1970s was that Mars was a dead planet. Probably, there is a strong oxidizer on its surface, which, after adding the nutrient medium to the soil, has decomposed it. Yes, radioactive gas was released, but it all happened in a completely non-biological way. This view was supported by most of the scientific world.

But not by Gilbert Levin. The scientist who created the experiment, sent it to Mars, and analyzed its results, continues to this day to believe that he has found life.

Professor Jupp Houtcooper has also intervened in this scientific controversy in recent years. In 2007, he published an article in Astrobiology, where he reinterpreted Levin’s results and concluded that they were compatible with the existence of life.

The scientist believes that the Viking missions found life, but the hypothetical organisms probably died later due to heating, which in combination with the existing hydrogen peroxide in the soil led to the destruction of cell walls. This explains why there was no repeatability in further analyzes with the Labeled Release experiment.

Most conservative researchers would not be satisfied with such difficult-to-prove assumptions. They would use the so-called “Occam’s razor” – a principle in science, according to which the simplest explanation is most likely.

If a phenomenon on Mars can be more easily explained in some non-biological way, it is much more likely than proposing a more complex assumption that involves hypothetical and as yet undescribed microorganisms.

Exceptional claims need exceptional evidence – and this is entirely true of the claim that there is life on Mars.

But the question of whether there is life on Mars is unlikely to be resolved easily, and more research will be needed over the next few years. The situation is complicated by the fact that after the Viking program, it took 40 years before another biological mission was sent to Mars.

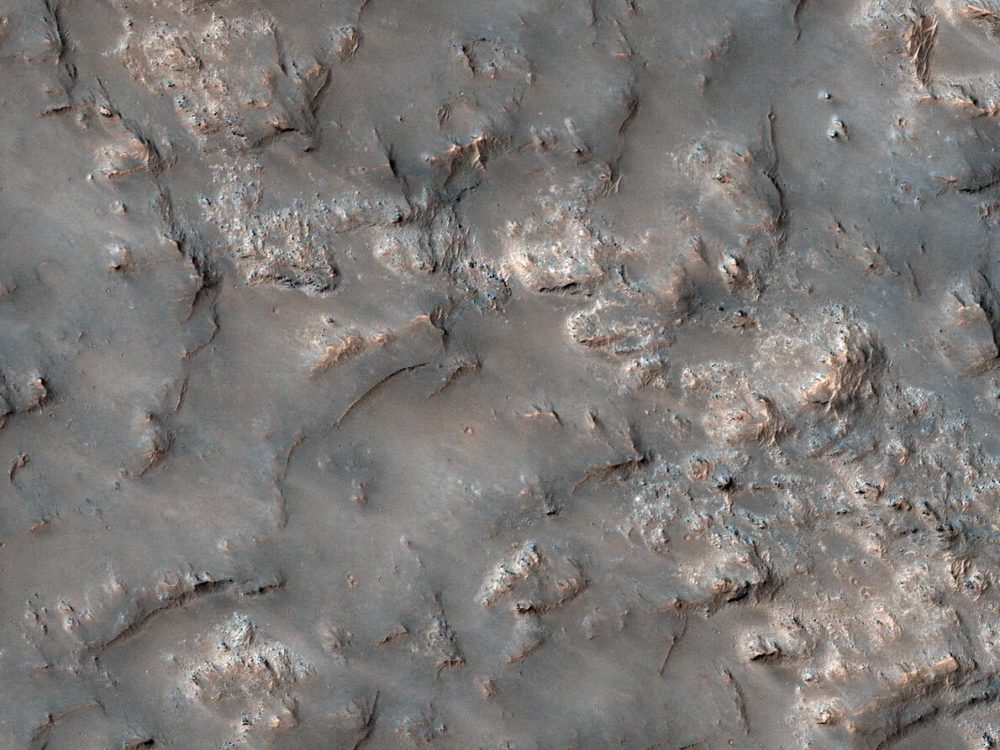

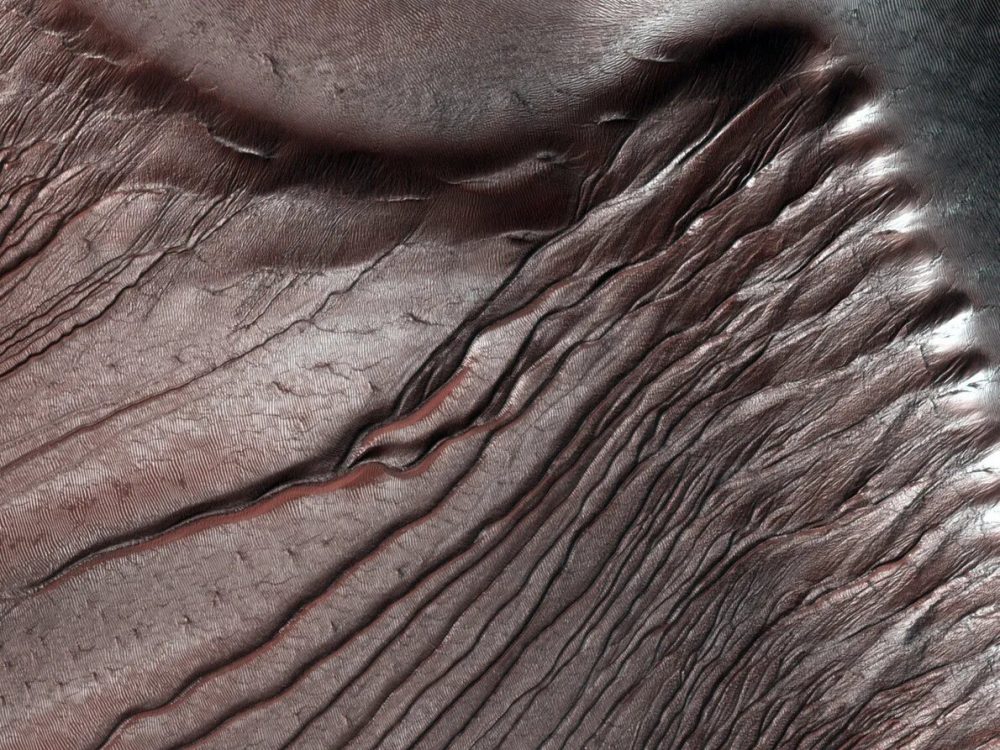

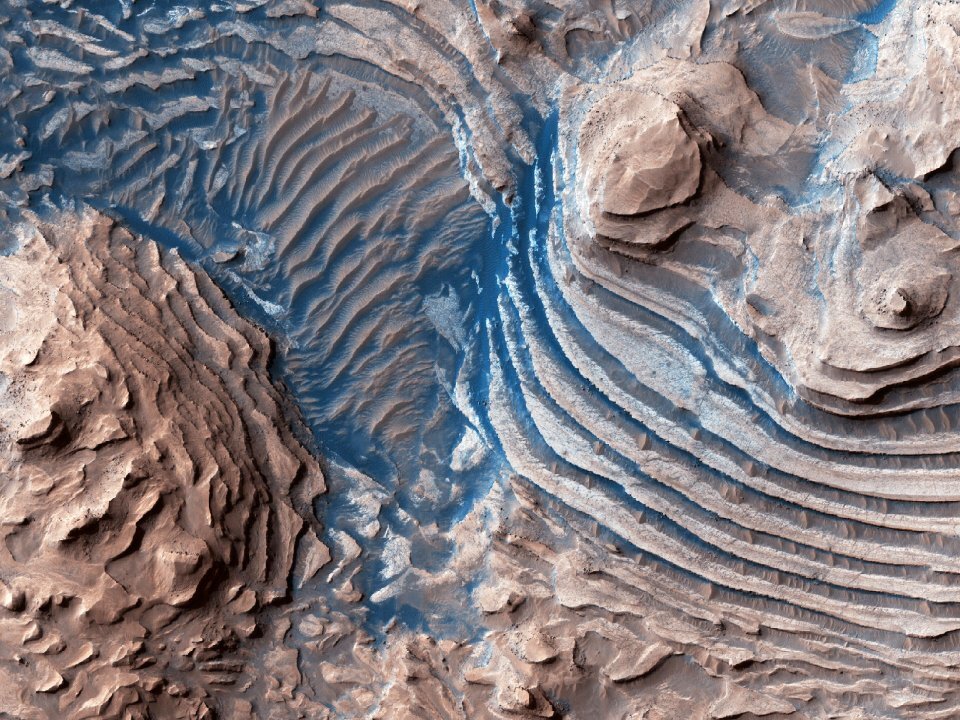

All other successful missions conducted in the last 20 years – “Mars Pathfinder”, the rovers “Spirit” and “Opportunity”, “Phoenix”, as well as “Curiosity” – all of them have been geological and have studied the geological history of the planet Mars, and not its biology.

Even so, we cannot overlook the endless stream of discoveries about the history of Mars that have been released in recent months and years. We learn more about the Red Planet with each passing year but the most pressing question at hand is whether Elon Musk and his SpaceX will be able to send humans to Mars and begin the first human colony as planned.

Join the discussion and participate in awesome giveaways in our mobile Telegram group. Join Curiosmos on Telegram Today. t.me/Curiosmos

Sources:

• Greicius, T. (2015, March 13). Mars Exploration Past Missions. Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/mars/missions/index-past.html?fbclid=IwAR0nYeniXQME6AVYVK2qQe52ztTvc3Udp1MtL9JGocMxIPN8YC9NZf_SLH0

• Houtkooper, J. M., & Schulze-Makuch2, D. (n.d.). A Possible Biogenic Origin for Hydrogen Peroxide on Mars: The Viking Results Reinterpreted. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/ftp/physics/papers/0610/0610093.pdf

• Steve Rakas, S. (n.d.). Retrieved November 30, 2020, from http://www.gillevin.com/mars.htm

• Viking 1. (n.d.). Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/missions/viking-1/