The mysteries, enigmas, and discoveries of ancient Egypt's underground labyrinth and how ancient writings helped make one of the most impressive discoveries in the history of Egypt.

Egypt is home to many mysteries. And while we have begun to excavate, document, and solve some of the greatest mysteries in history, there’s still plenty to do and explore in Egypt. Most of that is located right beneath our feet, beneath the golden sands of Egypt. Egypt has no shortage of stories of secret cities, imposing monuments, and elusive labyrinths. We recently commemorated Egypt’s underwater city, and we have written amply about its monuments and Pyramids. But Egypt is more than just that. The entire country can be viewed as a massive ancient encyclopedia, and each discovery and archeological site is another page that helps us understand history.

The Lost Labyrinth

What would you say if I told you that there was a massive labyrinth in ancient Egypt, hidden from sight, located beneath the surface? It is a structure that even surpasses the greatest of Pyramids erected in Egypt. Grandiose claims require even more significant evidence. And finding that evidence isn’t tricky at all. “This I have seen, a work beyond words. For if anyone put together the buildings of the Greeks and displayed their labors, they would seem lesser in both effort and expense to this labyrinth… Even the pyramids are beyond words, and each was equal to many mighty works of the Greeks. Yet the labyrinth surpasses even the pyramids.”

The above quote was penned down by Greek historian Herodotus who wrote in the 5 th century BC (‘Histories,’ Book, II, 148) of the existence of a massive temple home to more than 3,000 rooms covered in intricate paintings and hieroglyphics. It was a structure unlike any other. But it wasn’t just Herodotus who wrote about this sensational labyrinth in Egypt. Many other writers in antiquity described it in great detail. Strabo wrote about it, and Manetho, Pomponius Mela, and Diodorus Siculus described its magnificence.

Some of them even claimed to have witnessed the labyrinth with their own eyes. Herodotus perhaps described the labyrinth in the best way possible, revealing many of its unique and peculiar characteristics in his second book (Histories).

Herodotus and his description

Herodotus explained that “…it has twelve courts covered in, with gates facing one another, six upon the Northside and six upon the South, joining on one to another, and the same wall surrounds them all outside; and there are in it two kinds of chambers, the one type below the ground and the other above upon these, three thousand in number, of each kind fifteen hundred.

The upper set of chambers we ourselves saw;… but the chambers underground we heard about only… For the passages through the chambers, and the goings this way and that way through the courts, which were admirably adorned, afforded endless matter for marvel, as we went through from a court to the chambers beyond it, and from the chambers to colonnades, and from the colonnades to other rooms, and then from the chambers again to other courts.”

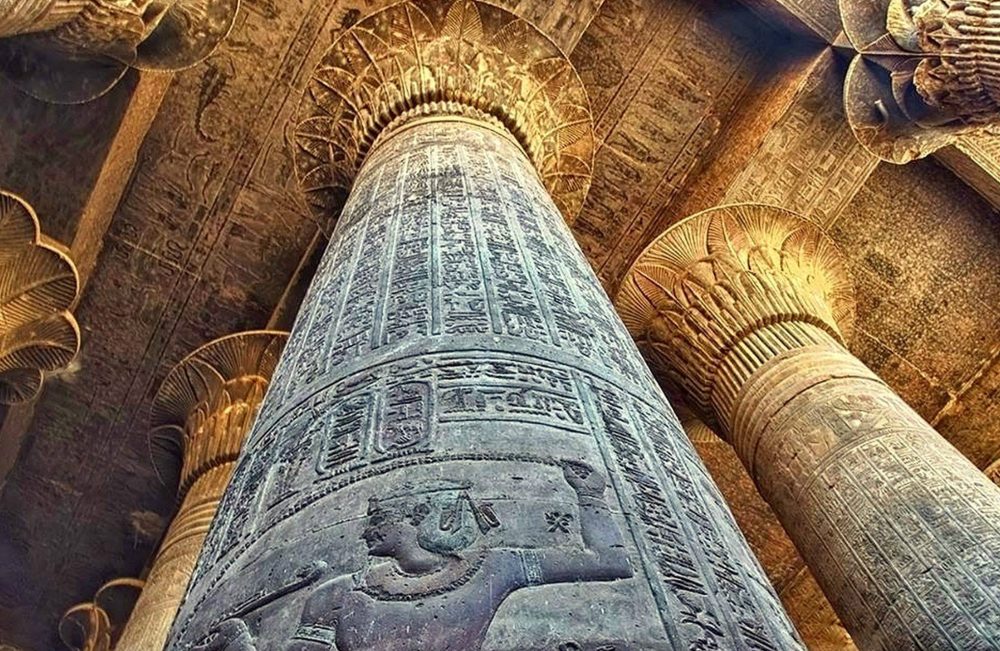

“Over the whole of these is a roof made of stone like the walls, and the walls are covered with figures carved upon them, each court being surrounded with pillars of white stone fitted together almost perfectly; and at the end of the labyrinth, by the corner of it, there is a pyramid of forty fathoms, upon which large figures are carved, and to this, there is a way made underground. Such is this labyrinth.”

What other writers of antiquity had to say

Strabo, a Greek geographer, philosopher, and historian, claimed to have visited the temple/labyrinth and seen its wonders with his own eyes. “Before the entrances, there lie what might be called hidden chambers which are long and many in number and have paths running through one another which twist and turn so that no one can enter or leave any court without a guide,” wrote Strabo in his work. Among other writers, the labyrinth was mentioned by Roman geographer Pomponius Mela in his work ‘Chorographia,’ The imposing labyrinth was also described by Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD) in his Natural History book where he wrote about the temple as a “bewildering maze of paths.”

Greek historian Diodorus Siculus reveals one of its most vivid descriptions, writing: “When one had entered the sacred enclosure, one found a temple surrounded by columns, 40 to each side, and this building had a roof made of a single stone, carved with panels and richly adorned with excellent paintings. It contained memorials of the homeland of each of the kings as well as of the temples and sacrifices carried out in it, all skilfully worked in paintings of the greatest beauty.” What’s even more interesting is that all of the above descriptions of the long-lost labyrinth are consistent, suggesting that this majestic place was not just a myth but a real place that existed some time in the distant past.

Finding the labyrinth

But if this imposing labyrinth is real, where is it located? To answer that, we turn to the Mataha expedition, a scientific mission that set out to find the labyrinth using state-of-the-art technology. To find the long-lost labyrinth location, this scientific mission turned to the writings by Herodotus, who revealed that the labyrinth was “situated a little above the lake of Moiris and nearly opposite to that which is called the City of Crocodiles.” If we travel to the city of Crocodilopolis, located on the western bank of Egypt’s Nile River, just between the river and Lake Moeris, we come across a fascinating site. South of the city of Crocodiles is an archeological site called Hawar, where the Pyramid of Amenemhat III, the last king of the 12th dynasty, stands in ruins.

It was precisely there where William Flinders Petrie made a significant discovery in 1889 as he uncovered a large stone plateau measuring 304m by 244m. Petrie identified the massive stone as the foundation upon which the ancient labyrinth once stood. But Petrie may have been wrong, and the Mataha expedition most likely proved that. They recalled what writers of antiquity, like Herodotus, Strabo, and Diodorus, had written about the labyrinth, explaining that it had a massive roof made of stone.

What if the massive stone that Petrie had found was not its foundation but the upper part of the roof? What if, beneath it, the labyrinth remains hidden? They used ground-penetrating radar to explore the site without damaging it to get to the bottom of the mystery.

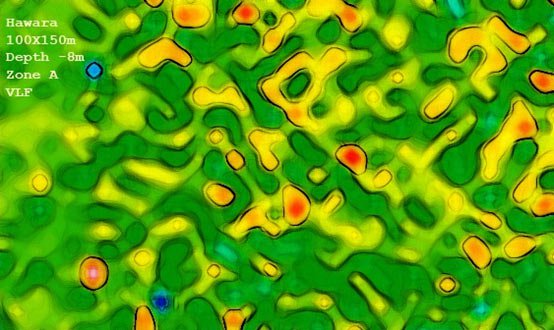

Twelve years ago, in 2008, and after receiving a special permit from the Supreme Council of Antiquities of Egypt, the researchers headed to the site and used ground-penetrating radar operated by the National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics to explore the area that Petrie had found in 1889. They found one of the most impressive discoveries in the history of Egypt: An extensive site located beneath the surface with vast chambers, halls, and walls several meters thick. At a depth of around 10 meters, a massive grid structure made of a material the experts argue is granite.

The scans confirmed that writers of antiquity had mentioned in the distant past, indicating that there was a massive, unexplored structure located beneath our feet that had remained undisturbed for millennia. Their discoveries were published in the journal NRIAG, and the results were presented during a lecture at Gent University in October 2008. Since 2008, the site has not been studied nor explored for reasons that remain shrouded in mystery.

Join the discussion and participate in awesome giveaways in our mobile Telegram group. Join Curiosmos on Telegram Today. t.me/Curiosmos