Beneath the streets of Aleppo, under the hills of Turkey, and across the plains of Mesopotamia lie the bones of cities long gone. Not buried by nature always, sometimes by choice. Sometimes layered on purpose. These are places where people didn’t just return to rebuild after collapse — they stayed put and built again, directly on top of the past.

The phenomenon of ancient cities built on top of each other is not a quirk of history. It is one of the most consistent and revealing patterns in the archaeology of early civilization. At sites like Çatalhöyük, Tell Brak, and Jericho, we find stacked layers of mudbrick, ash, and stone that represent thousands of years of unbroken occupation. When I look back at these, I kind of feel that every layer tells a story. And it is not just one of progress, but one of survival, one of adaptation, and the human instinct to stay grounded in place.

But before I go any further, I would like to take a moment to explain the words “tell,” “tepe,” and “tappeh”.

What do “tell,” “tepe,” and “tappeh” mean?

If you’ve ever come across names like Tell Brak, Göbekli Tepe, or Tappeh Sialk, you might have wondered what those words mean. So, they’re not just names. They’re clues about the history hidden beneath the surface.

In archaeology, a “tell” is an artificial mound formed by layers of human settlement built up over time. The word tell comes from Arabic and means “hill.” These mounds form when people live in the same place for hundreds or even thousands of years. Each time a building collapses or burns down, the debris stays behind. New buildings go up right on top. Over time, the site rises higher and higher, creating a mound filled with history.

In Turkish, the same kind of mound is called a “tepe,” which also means “hill.” That’s why we see names like Göbekli Tepe in modern-day Turkey. The name literally translates to “Potbelly Hill.”

In Persian (Farsi), the word is “tappeh.” In Iran, many ancient sites use this term, like Tappeh Sialk or Tappeh Hesar. Just like tells and tepes, these are mounds formed from ancient cities that were built, destroyed, and rebuilt over and over again.

So while the words are different, they all point to the same idea. Whether it’s a tell, tepe, or tappeh, it means you’re looking at a place where people stayed for a long time, rebuilding their homes on the same ground again and again. And underneath each one lies layer after layer of forgotten history.

Why did people rebuild in the same place?

I will try and explain this the best way I can so it makese sense.

But before we start I would like to clear somehing: rebuilding on top of older ruins wasn’t just about tradition. It made practical sense for a lot of reasons, and those reasons were often tied to survival.

First, there was the need for water. Fresh sources like rivers, springs, and wells didn’t move. If a site had good access to water, people would come back to it again and again. In dry regions, staying close to reliable water could mean the difference between life and death.

Then there was the value of fertile land. Soil that could support crops wasn’t available everywhere. Once people learned how to work the land in a specific place, it made sense to stay there. Moving away could mean losing hard-earned knowledge about how to survive in that environment.

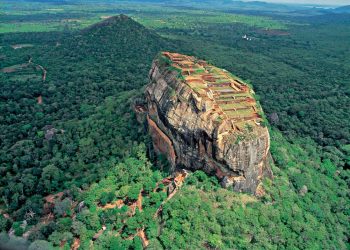

Geography also played a role. Many early cities were built on hills or near mountain passes, where they had a better view of the surrounding area and could defend themselves more easily. Others were near trade routes, allowing them to control movement and commerce. Giving up those positions would have been a big loss.

Materials mattered too. Building supplies like stone, timber, and mudbrick were valuable and not always easy to find. After a disaster — whether from war, fire, or time — people often reused whatever they could. Rebuilding on the same ground saved effort and made use of what was already there.

Finally, there was a deep sense of connection to place. People returned to where they had grown up, where their ancestors were buried, where stories had been passed down. These locations held emotional weight. Staying put wasn’t just practical. It helped people hold on to who they were.

Çatalhöyük: Where life and memory were stacked in mudbrick

Without a doubt, one of my favorites.

In the heart of what is now central Turkey lies one of the earliest known cities in human history — Çatalhöyük. First settled around 7500 BCE, this Neolithic site grew into a dense community of thousands. What makes it so fascinating isn’t just its age, but how it was built and rebuilt over time.

People at Çatalhöyük lived in tightly packed mudbrick houses. Instead of streets, they walked along rooftops, entering their homes through holes in the ceiling using ladders. When a house was abandoned or collapsed, a new one was constructed directly on top of the old foundation. Over the span of about 1,200 years, this cycle created 18 layers of construction, stacked one above the other.

The layers weren’t just architectural. They were deeply personal. Families buried their dead beneath the floors of their homes. That meant every new house was also resting on the memory of those who had lived there before. Çatalhöyük was more than a city. I feel it was a place where memory, ancestry, and everyday life were physically tied together. Layer across layer.

Tell Brak: A city that grew from a sacred center

Over in northeastern Syria stands Tell Brak, another key to understanding the layered nature of ancient cities. It began as a small settlement around 6000 BCE, but over time, it developed into one of the first large urban centers in the world.

Its early structures were likely ceremonial — shrines and sacred enclosures that marked the site as spiritually important. As the population grew, homes, administrative buildings, and roads began to form around these sacred spaces. And like at Çatalhöyük, the site was rebuilt again and again as each generation adapted to new conditions.

Some of Tell Brak’s layers are thin, representing short-term activity. Others are deeper, the result of longer, more stable phases of occupation. What holds it all together is continuity. Despite changes in leadership, culture, and environment, people kept coming back. They didn’t abandon the place when things got hard. They built over it and moved forward.

Tepe Gawra: Sacred patterns that never faded

North of Mosul in modern-day Iraq lies Tepe Gawra, a site known not just for its long history, but for how that history was shaped by religious life.

Tepe Gawra was occupied from about 5000 BCE and contains 16 layers of construction. As temples fell out of use, new ones were often built on top of them. In some cases, the exact layout was preserved, even as decorative elements or materials changed. This suggests more than just practicality. It points to a deep respect for sacred space.

Generations of people reused the same ground to worship, plan, and gather. The buildings changed, but the meaning behind them did not. Tepe Gawra shows how spiritual identity was literally rooted in place.

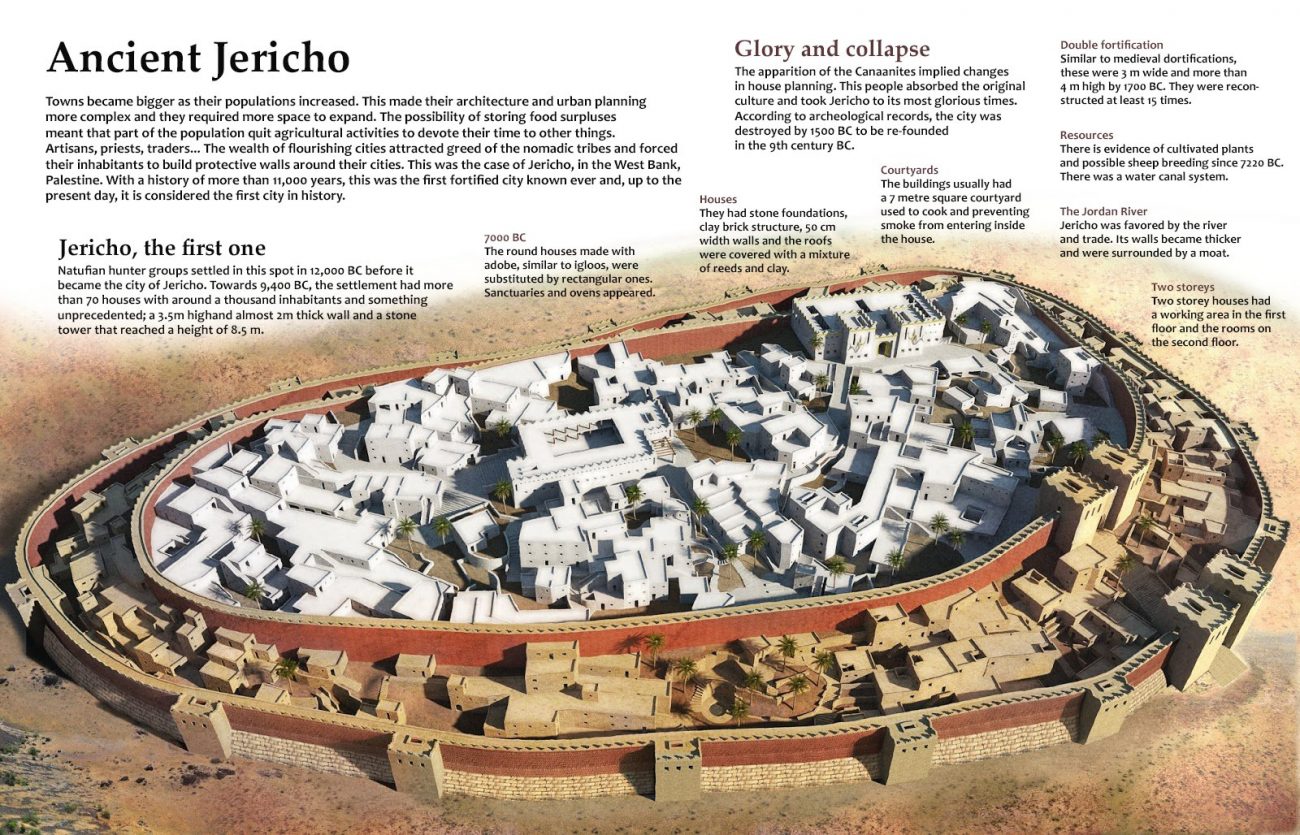

Jericho: A city layered with 11,000 years of survival

Few places on Earth have been occupied as long as Jericho. Located near the Jordan River, it is one of the oldest continually inhabited cities in the world. Excavations at Tell es-Sultan, the ancient core of Jericho, reveal more than 20 layers of human settlement dating back to around 9000 BCE.

One of the most striking finds is a massive stone tower and wall system that dates to the Neolithic era, long before similar structures appeared elsewhere. As each civilization passed through, it built on top of what came before. Homes, fortifications, and tools from different ages now lie stacked in the soil, preserved in a vertical record of resilience.

Jericho isn’t just a story about one people or one culture. It’s a case study in continuity. Despite conquest, natural disaster, and political change, the city remained. The location mattered more than the name or ruler of the day.

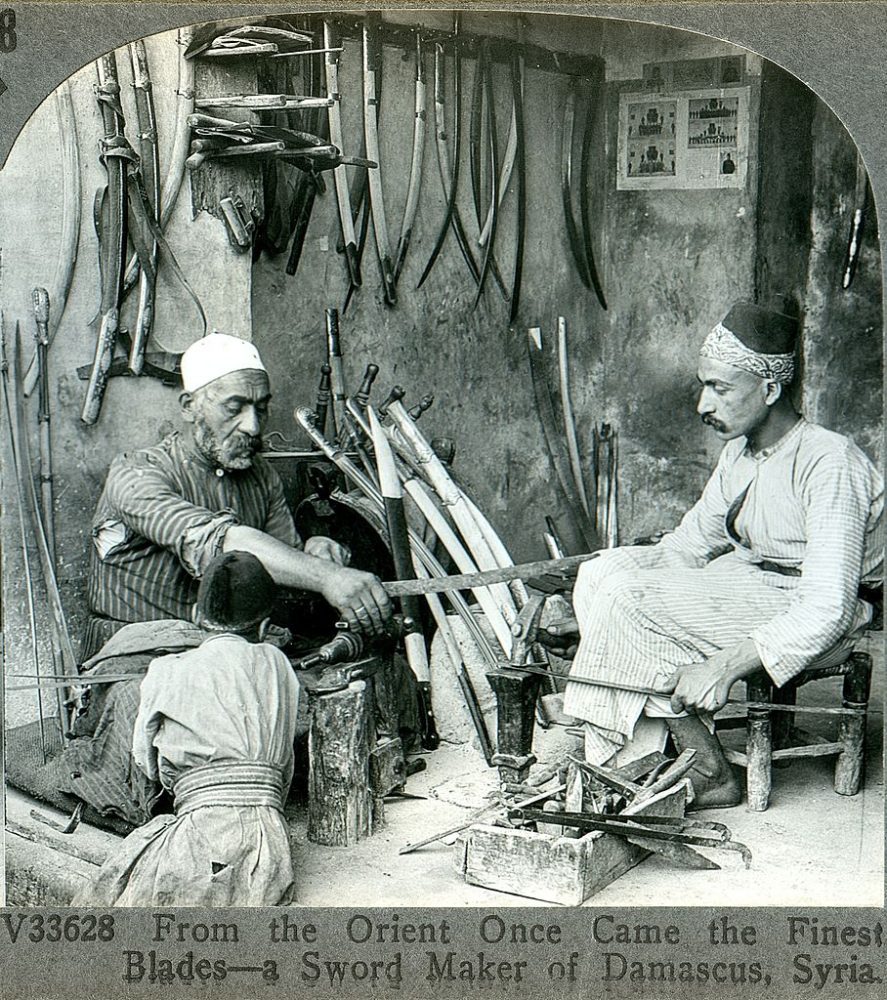

Aleppo and Damascus: Where history still breathes beneath the surface

Some ancient cities are still very much alive. Aleppo and Damascus, both located in Syria, are among the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities. Unlike Çatalhöyük or Tell Brak, these are not archaeological sites frozen in time. They are living, breathing places where people still go to work, shop in markets, and pray in centuries-old mosques.

But beneath those streets lie the buried remains of Bronze Age buildings, Roman roads, and medieval fortifications. Excavations are difficult because life continues above them. Still, what’s already been uncovered tells a clear story: layer after layer, civilization after civilization, all built in the same place.

In cities like Aleppo and Damascus, I dont see the past as being buried and forgotten. I see it built into the streets and buildings people still use today. The layering never really stopped.

Staying in place wasn’t always a choice. Sometimes, it was the only option.

So what do we learn from the amazing examples above? Not every ancient city was rebuilt because people wanted to keep a tradition alive. Sometimes they stayed because the ground still gave them what they needed. There was a spring nearby. Or the fields still produced grain. Or the road still led to trade.

But other times, they stayed because the land had become part of who they were. The memory of ancestors, rituals, and buried homes gave the place weight. Walking away would have meant walking away from everything that gave their lives shape.

That’s why we find temples built over older temples. Streets rebuilt along the same lines. City walls rising again where they once fell. In other words, this wasn’t nostalgia. It was actually a way to keep going while staying grounded in what came before.

Technology is now catching up to what was always there

We’ve known for centuries that cities were built on older cities. But only recently have we started to understand just how many layers are hidden beneath the surface, and how much we’ve missed by only looking at what we can see.

With ground-penetrating radar, LIDAR, and other tools, archaeologists are finding older foundations below familiar sites. What we thought was the beginning turns out to be the middle. Cities like Troy and Uruk have become deeper, both in time and meaning, thanks to what these tools reveal. But LiDAR has made some amazing discoveries in the Amazn rainforest as well, where it practically discovered traces of a long-lost civilization whose traces were buried beneath dense layers of vegetation.

What I also find extremly intersting and peculiar is that in places like Jericho or Damascus, the remains of dozens of earlier settlements lie just below modern streets. They’re not ruins in a museum. They’re still part of the living city, buried but not gone.

Every time a shovel hits stone in these places, it brings up more than debris. It brings up decisions of the ancestors. To rebuild. To stay. To remember. And thats kind of what Zahi Hawass told me during one of my podcasts when I asked him about Giza, and how much “stuff” was still buried beneath the surface there. He replied saying that if you were to excavate in present-day Giza, youd likley come up with an item of two of the ancient Egyptian civilization. And I guess this applies to other sites across the world.