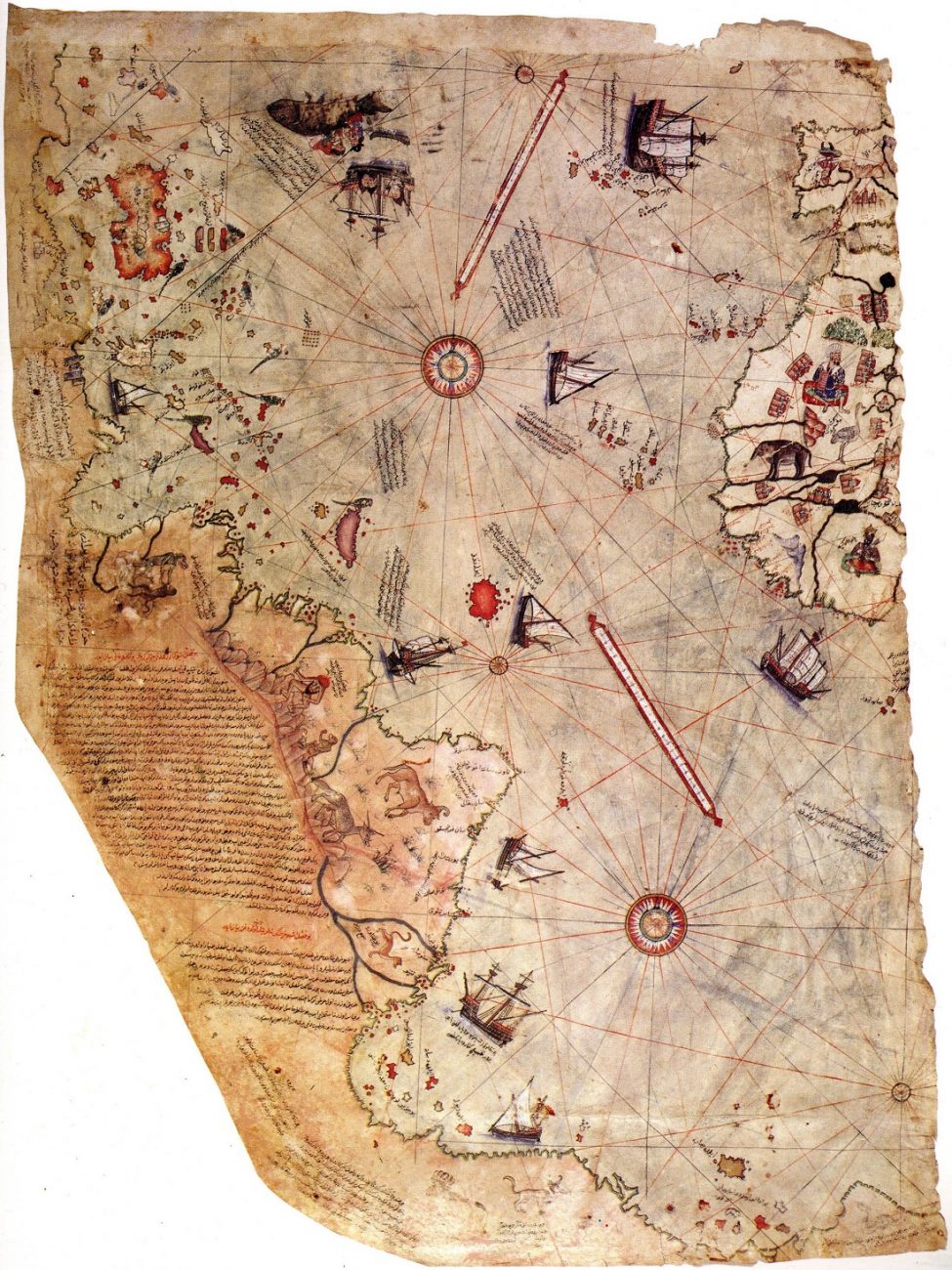

Does the Piri Reis map of Antarctica really depict the continent without its ice sheet? Over the years, this fragmentary 16th-century map has sparked intense debate among researchers, skeptics, and historians. Created by Ottoman admiral Piri Reis in 1513 and based on earlier source material, some claim it shows Antarctica in unexpected detail—centuries before it was officially discovered. But what do the map, its inscriptions, and official evaluations really reveal?

A mysterious map from the Age of Exploration

Throughout history, many maps have puzzled historians, but few as much as the Piri Reis map of Antarctica. Composed in 1513 by Ottoman admiral and cartographer Piri Reis, the map was drawn on gazelle skin parchment and is believed to have been presented to Sultan Selim I in 1517. Today, only about one-third of the original map survives.

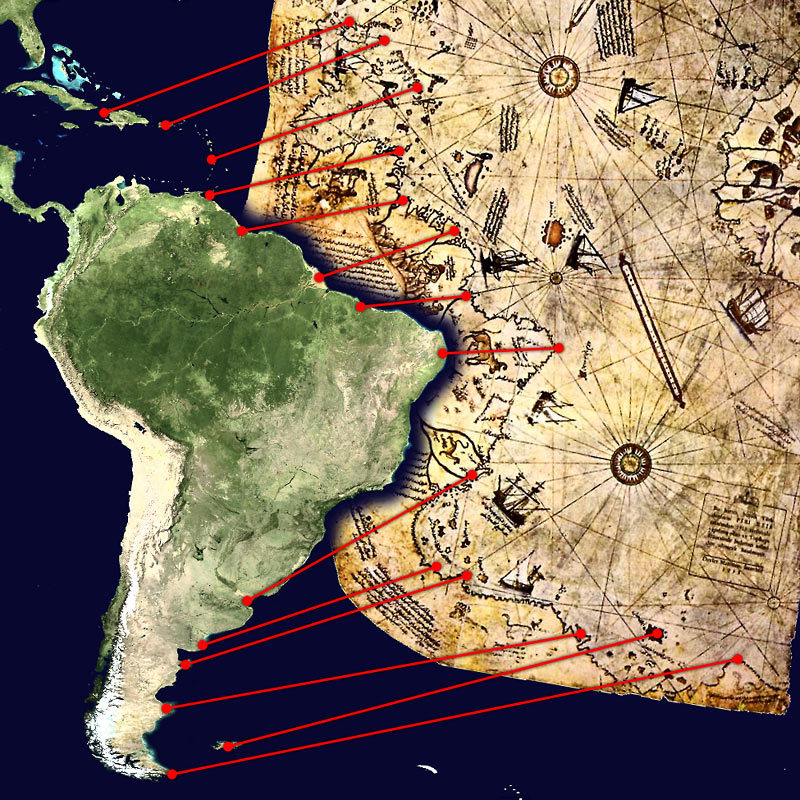

This surviving portion shows the western coasts of Europe and North Africa, the eastern coast of South America, and several Atlantic islands, including the Azores and Canary Islands. The map even includes the mythical island of Antillia and possibly parts of Japan. But what continues to draw attention is the southernmost section—claimed by some to show a portion of Antarctica, possibly before it was covered in ice.

According to Piri Reis, older sources were key

The map contains detailed inscriptions from Piri himself. In the map’s legend, he notes that his chart was compiled from about twenty older source maps, including:

-

Eight Ptolemaic maps

-

An Arabic map of India

-

Four recently drawn Portuguese maps

-

A map by Christopher Columbus of the western lands

From Inscription 6 on the map, Piri Reis wrote:

“From eight Jaferyas of that kind and one Arabic map of Hind [India], and from four newly drawn Portuguese maps which show the countries of Sind [now in modern day Pakistan], Hind and Çin [China] geometrically drawn, and also from a map drawn by Qulūnbū [Columbus] in the western region, I have extracted it. By reducing all these maps to one scale this final form was arrived at…”

For decades, the precision and structure of the map—especially in the southern region—have sparked speculation. Why do parts of the map appear to align with the subglacial terrain of Antarctica? Could the Piri Reis map of Antarctica truly be based on ancient knowledge of a now-hidden coastline?

The Antarctica question

Antarctica has not always been frozen. In geological terms, ice appeared relatively recently—around 35 million years ago. Prior to that, the continent remained largely ice-free for roughly 100 million years. Scientists believe the shift to an ice-covered Antarctica occurred over about 100,000 years.

Today, nearly 98% of the continent is covered by ice, averaging nearly two kilometers thick and obscuring most of the natural landscape. The first known navigation into Antarctic waters occurred in 1772 by British explorer James Cook, but he encountered only sea ice and never saw land. It wasn’t until 1819 that the landmass itself was officially discovered by Fabián von Bellingshausen.

The real breakthrough in understanding Antarctica’s land came in 1950, when the American expedition “Deep Freeze” used seismic data to begin mapping what lay beneath the ice. So how could any earlier chart, especially one from 1513, show these features?

A claim that caught the attention of the U.S. Air Force

In 1960, Professor Charles Hapgood of Keene College reached out to the U.S. Air Force, asking them to evaluate the map. What followed were a series of surprising responses.

8 RECONNAISSANCE TECHNICAL SQUADRON (SAC)

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE

Westover Air Force Base

MassachusettsReply to Attn of RTC

6 July 1960

Subject: Admiral Piri Reis World Map

To: Prof. Charles H. Hapgood

Keene Teachers College

Keene, New HampshireDear Professor Hapgood,

Your request for evaluating certain unusual features of the Piri Reis World Map of 1513 by this organization has been reviewed.

The claim that the lower part of the map portrays the Princess Martha Coast of Queen Maud Land Antarctic and the Palmer Peninsula is reasonable. We find that this is the most logical and, in all probability, the map’s correct interpretation.

The geographical detail shown in the lower part of the map agrees remarkably with the seismic profile results made across the top of the ice cap by the Swedish-British-Norwegian Antarctic Expedition of 1949.

This indicates the coastline had been mapped before the ice cap covered it.

The ice cap in this region is now about a mile thick. We have no idea how the data on this map can be reconciled with the supposed state of geographical knowledge in 1513.

Harold Z. Ohlmeyer

Lt. Colonel, USAF

The interpretation that part of the map shows Queen Maud Land—a portion of the Antarctic coastline—struck some researchers as too detailed to be accidental. Hapgood then followed up with further correspondence, which brought an even more in-depth reply.

8 RECONNAISSANCE TECHNICAL SQUADRON (SAC)

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE

Westover Air Force Base, Mass.14 Aug 61

Mr. Charles H. Hapgood

Keene Teachers College

Keene, N.H.Dear Professor Hapgood:

It is not very often that we have an opportunity to evaluate maps of ancient origin. The Piri Reis (1513) and Oronteus Fineaus [sic] (1531) maps sent to us by you presented a delightful challenge, for it was not readily conceivable that they could be so accurate without being forged. We accepted this challenge with added enthusiasm and have expended many off-duty hours evaluating your manuscript and the above maps. I am sure you will be pleased to know we have concluded that both of these maps were compiled from accurate source maps, irrespective of dates. The following is a brief summary of our findings:

The solution of the portolano projection used by Admiral Piri Reis, developed by your class in Anthropology, must be very nearly correct, for when known geographical locations are checked about the grid computed by Mr. Richard W. Strachan (MIT), there is remarkably close agreement. Piri Reis’ use of the portolano projection (centered on Syene, Egypt) was an excellent choice, for it is a developable surface that would permit the relative size and shape of the earth (at that latitude) to be retained. We believe that those who compiled the original map had an excellent knowledge of the continents covered by this map.

As stated by Colonel Harold Z. Ohlmeyer in his letter (July 6, 1960) to you, the Princess Martha Coast of Queen Maud Laud, Antarctica, appears to be truly represented on the southern sector of the Piri Reis map. The agreement of the Piri Reis Map with the seismic profile of this area made by the Norwegian-British-Swedish Expedition of 1949, supported by your solution of the grid, places beyond a reasonable doubt the conclusion that the original source maps must have been made before the present Antarctic ice cap covered the Queen Maud Land coasts.

Our opinion that the accuracy of the cartographic features shown in the Oronteus Fineaus [sic] Map (1531) suggests, beyond a doubt, that it also was compiled from accurate source maps of Antarctica, but in this case of the entire continent. Close examination has proved the source maps must have been compiled at a time when the landmass and inland waterways of the continent were relatively free of ice. This conclusion is further supported by comparing the Oronteus Fineaus [sic] Map with the results obtained by International Geophysical Year teams in their measurements of the subglacial topography. The comparison also suggests that the original source maps (compiled in remote antiquity) were prepared when Antarctica was presumably free of ice. The Cordiform Projection used by Oronteus Fineaus [sic] suggests the use of advanced mathematics. Further, the Antarctic continent’s shape suggests the possibility, if not the probability, that the original source maps were compiled on a stereographic or gnomic type of the projection (involving the use of spherical trigonometry).

We are convinced that the findings made by you and your associates are valid. They raise fundamental questions affecting geology and ancient history, questions that certainly require further investigation.

We thank you for extending us the opportunity to have participated in the study of these maps. The following officers and airmen volunteered their time to assist Captain Lorenzo W. Burroughs in this evaluation: Captain Richard E. Covault, CWO Howard D. Minor, MSgt Clifton M. Dover, MSgt David C. Carter, TSgt James H. Hood, SSgt James L. Carroll, and A1C Don R. Vance.

LORENZO W. BURROUGHS

Captain, USAF

Chief, Cartographic Section

8th Reconnaissance Technical Sqdn (SAC)

Westover Air Force Base, Massachusetts

These letters raised questions that are still being discussed today. If the Piri Reis map of Antarctica does depict a coastline now buried under ice, how was that knowledge obtained in 1513—or long before? And who might have created the earlier maps that Piri compiled?

Could the map really be Antarctica?

Not all scholars accept the idea. Critics argue that the supposed Antarctic coastline on the Piri Reis map could be a misinterpretation of the southern tip of South America. Some propose that the unusual southern landmass may represent coastal Patagonia, the Falkland Islands, or even a stylized extension of the South American continent.

As pointed out by geologist Steven Dutch, there are two major discrepancies:

-

The landmass believed to be Antarctica appears hundreds of kilometers north of its true location

-

The Drake Passage—the body of water separating South America from Antarctica—is missing entirely

Additionally, inscriptions on the map describe the southern region as having a warm climate, which clearly conflicts with what we know about Antarctica, both now and in the past.

Other researchers argue that the map may have been shaped by copying and recopying over centuries, introducing distortions. Still, the debate continues, especially among alternative historians who suggest the map points to a lost civilization with advanced geographical knowledge.

So what does the Piri Reis map of Antarctica actually show?

Professor Hapgood believed it was based on source material that could date back to before 4000 BCE, long before any known civilization had the tools or knowledge to chart something as remote as Antarctica. If that’s the case, it would force us to rethink everything we know about early human history.

But that idea remains highly speculative at best. There’s no confirmed trace of these ancient source maps and no solid evidence of the civilization that might have created them. I mean, it would be beyond awesome, but we have to stick to what we have in regard to factual data.

Nonetheless, there are many explanations. Some say the southern landmass is just a distorted version of South America. Others think Piri Reis and his sources may have filled in the gaps with guesswork, as mapmakers often did when faced with the unknown.

Maybe the answer is somewhere in between. But I guess that even though this is not the first time this curious item was brought up in an internet discussion, the Piri Reis map of Antarctica still captures attention today. And it is not because it gives us clear answers, but because it doesn’t. Whether it’s a glimpse of forgotten knowledge or just an early cartographic mistake, this 500-year-old map keeps raising the same question: how much did ancient people really know?