What if civilization didn’t begin with cities or writing, but with memory and the sky? What if the first civilizations were older than we think?

For generations, we were taught that civilization began in Sumer and Egypt — around 3000 BCE — when humans finally settled, wrote laws, and built cities. That idea shaped everything from textbooks to popular documentaries. But over the last few decades, archaeologists have uncovered something far older. Massive stone temples, planned settlements, and mysterious ceremonial structures have emerged from beneath the soil of Turkey, Syria, and Jordan. T

hey tell a story few were expecting: that the first civilizations were older than we think, and that they didn’t begin with farming or rulers, but with ritual, alignment to the stars, and shared cultural memory.

These sites are forcing historians to rethink not only when civilization began, but what it even means to be civilized.

The old narrative is crumbling

Civilization, we’ve been told, followed agriculture. Once people farmed, they stored grain. With storage came surplus. With surplus came hierarchies, trade, religion, and writing. But this neat progression is being disrupted by evidence that large, organized communities existed long before farming, and long before anyone thought complex societies were possible.

The first real cracks in the timeline appeared in the 1990s, when excavations at a hilltop in southeastern Turkey revealed a set of carved stone enclosures unlike anything seen before. But that was just the beginning. And as one of my favorite authors say it quite often, “things keep on getting older.”

Tell Qaramel: Towers before the plow

In northern Syria, archaeologists found something unexpected: a site called Tell Qaramel, dating back to around 10,700 BCE. That’s nearly 7,000 years before the pyramids. Here, multiple circular stone towers were constructed with carefully laid foundations and multi-level floors, all during a time when people were still hunting and foraging.

There was no farming, no pottery, and no writing. Yet the structures show planning, cooperation, and a clear sense of permanence. They challenge the idea that architectural sophistication had to wait for agriculture. They’re one of the first signs that the first civilizations were older than we think, and organized in ways we still don’t fully understand. I do not think that people are actually aware of the number of amazing, incredible, and mind-boggling sites that exist in Iraq.

Çayönü: Ritual and order before state control

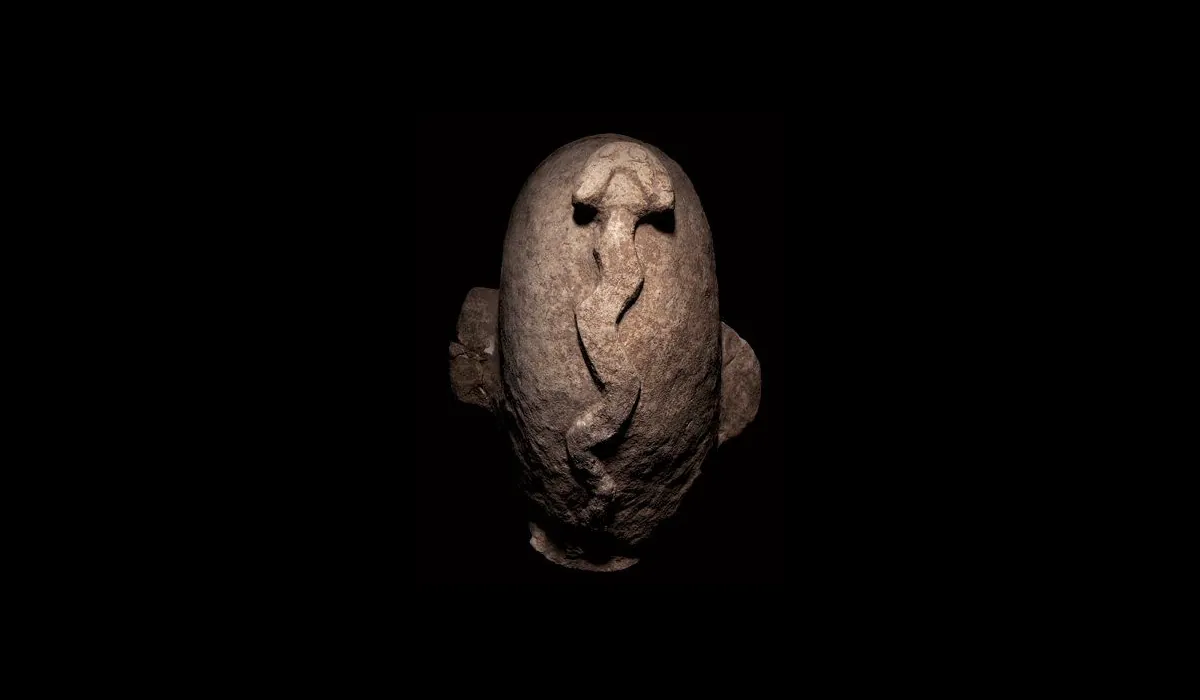

South of Tell Qaramel lies another site, Çayönü, which was occupied between 8800 and 7000 BCE. The layout was astonishingly deliberate. Rectangular homes arranged along shared paths, communal buildings with stone-paved floors, and — perhaps most disturbingly — a room filled with rows of human skulls embedded in the floor.

This wasn’t chaos. It was ritual. Scholars now believe this “skull building” served as a ceremonial site, part of a belief system passed from generation to generation. There’s no evidence of kings or taxation, yet the people of Çayönü lived with structure, meaning, and continuity. It’s one more clue that the first civilizations were older than we think, and less dependent on domination than we assumed.

Wadi Faynan: City behavior without a city

In the Jordanian desert, where survival today is a challenge even with modern tools, lies the site of Wadi Faynan — a settlement nearly 10,000 years old. It lacks walls, palaces, or temples, but it shows something else: early irrigation, cooperative labor, and multi-room housing.

There was no ruling class. No evidence of military enforcement. Yet people worked together to manage water, food, and construction. This type of social coordination has long been associated with formal city-states — but Wadi Faynan had none. It’s a quiet but powerful example that the first civilizations were older than we think, and may have valued function over formality.

Nevalı Çori: The first temples?

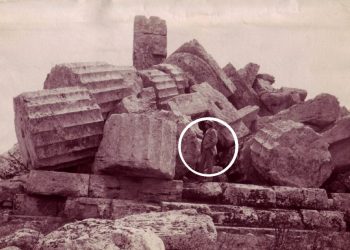

Before Göbekli Tepe stunned the world, a nearby site called Nevalı Çori hinted at a forgotten chapter in human history. Dated to around 8500 BCE, this small village held something remarkable: carved pillars, humanoid statues, and a structure that appears to have been a ritual hall or temple.

All of this happened before the widespread use of farming, metal, or permanent cities. The stonework was advanced. The figures were symbolic. The layout suggested planning. It was not just shelter — it was a sacred space.

Nevalı Çori is one of several sites now revealing that the first civilizations were older than we think, and driven as much by shared meaning as by material need.

What were these people building — and why?

Ok, but let’s step back for a minute and ask an important question. Why? If not for survival, then what drove people to carve massive stones, align temples to the solstice, and plan settlements with symmetry? These were not random experiments. They reflect something deeper: the need to remember, to pass down knowledge, to make sense of death, stars, and time itself.

In place after place, from Göbekli Tepe to Karahan Tepe, we find symbolism without writing, cooperation without kings, and architecture without agriculture. These early builders were not primitive. They were highly intelligent, spiritually driven, and deeply aware of their place in the world.

If you ask me, the evidence is mounting: and we have to start rewriting our history books and acknowledge that the first civilizations were older than we think, and rooted not in wealth or war, but in meaning.

Rethinking the definition of civilization

But it is also time for one more thing. We need to redefine the word for “civilization”. For too long, civilization has been defined by what leaves behind the most impressive ruins, pyramids, palaces, writing systems. But this definition overlooks something crucial: intention.

What if a circle of carved pillars in Turkey carries more civilizational meaning than a walled city? What if skulls arranged in a sacred floor say more about culture than a stone tablet of taxes? What if the first civilizations were older than we think, simply because they were never about power, but about… say… memory?

We are not discovering “primitive ancestors.” We are uncovering the deep roots of cultural intelligence.

A future built on forgotten pasts

Every new find and every carved totem, buried tower, and stone map of the stars adds to a growing truth: the beginning of civilization didn’t start with kings. It started with questions. Who are we? Where do we go when we die? What moves in the sky above?

The answers were written not in ink, but in stone, passed silently from hand to hand for thousands of years. And they remind us that the first civilizations were older than we think, and perhaps wiser, too.

So guess it is time to finally acknowledge that the story of human civilization doesn’t begin in 3000 BCE. It begins in silence, in ritual, in stones aligned with the stars. Long before cities and scribes, people were building structures that spoke to the soul, not the state. If we want to understand where we come from, we must look beyond kings and kingdoms. The first civilizations weren’t lost. They were simply buried — waiting for us to listen. Waiting for us to discover.