In the shallows off Yonaguni, Japan’s westernmost island, the sea floor drops away into shadows. A few meters down, the reef opens to reveal something vast. It doesn’t resemble a coral shelf or a sloping rock bed. Instead, divers encounter massive ledges, flat platforms, and vertical faces that look like walls. Underwater light filters across broad stone steps. The geometry is startling.

This formation, often called the Yonaguni Monument, rests around twenty-five meters below the surface. It stretches roughly 150 meters in length, with a width of about 40 meters. Sharp corners and straight lines define its structure. Some of the edges look machined. One side has what appears to be a long trench running parallel to a clean rock face. Others contain isolated monoliths that rise from the seabed like carved sentinels.

The site was discovered in 1986 by Kihachiro Aratake, a local dive tour operator. He had been scouting the area for hammerhead sharks when he spotted what looked like a manmade platform beneath him. The stone seemed too precise. He surfaced and reported what he saw. Word spread quickly. Within a few years, marine geologists and fringe theorists alike were descending with cameras, tape measures, and notebooks.

The first impressions

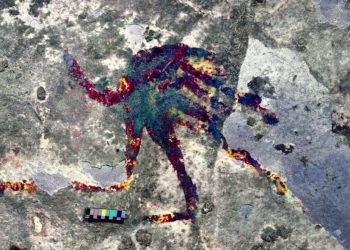

Divers returning from Yonaguni often speak of disorientation. The regularity of the lines confuses depth perception. Some liken it to swimming over an ancient city plaza. Flat terraces run horizontally for several meters before dropping off into deep, squared recesses. In certain places, ledges resemble steps. One stretch of stone looks like a long avenue cut straight through the rock.

Fish dart along the edges, but coral is sparse. The formation is clean, almost sterile. Light clings to the surfaces in the early morning, casting angular shadows. When photographed from above, the whole structure looks as if it was designed, and not eroded.

Many visitors return convinced that what they saw was built. Some claim to notice channels or corner joints. Others insist they saw signs of wear or alignment too precise to be natural. Still, these observations remain anecdotal. No excavation has been conducted. Everything known about the site comes from visual study and surface dives.

Natural geology or optical illusion

The most widely accepted view among geologists is that the site is entirely natural. The rock is sandstone, layered horizontally and subject to tectonic uplift. Over time, pressure from seismic activity cracked the stone along joint lines, producing right angles. Erosion then exploited these fractures, creating straight edges and geometric shapes that only appear artificial.

What I find interesting is that in the Ryukyu Islands, similar formations can be seen above water. The cliffs along parts of Yonaguni’s coastline break into natural stair-step shapes. These exposed layers fracture cleanly, sometimes forming platforms that mimic steps or floors. The region’s seismic instability makes it likely that large blocks of stone were shifted, tilted, or dropped into place by tectonic activity.

Geologists point out that humans tend to perceive symmetry and intention where there is only chance. Patterns formed by natural processes are often mistaken for design, especially underwater, where visibility and orientation distort perception. In the case of Yonaguni, the size of the formation and its unfamiliar setting amplify this effect.

The case for deliberate shaping

Despite geological explanations, some researchers believe that the underwater formation may have been modified by human hands. One of the most vocal proponents of this theory is Masaaki Kimura, a marine geologist who has surveyed the site extensively. He argues that the stone faces include features that go beyond erosion and fracture.

Kimura’s team has mapped what they interpret as stairs, platforms, and even a possible relief carving of a face. He suggests the site could be the remains of a sunken temple or civic structure, possibly dating back over 10,000 years. According to his hypothesis, sea levels rose dramatically at the end of the last Ice Age, flooding low-lying settlements and preserving their foundations underwater.

The idea is not without precedent. Other submerged sites, such as those off the coast of India and Greece, have revealed ancient ruins buried beneath the sea. In those cases, artifacts, walls, and datable material have confirmed human occupation. But no such evidence has surfaced at Yonaguni.

Critics of Kimura’s work argue that his interpretations rely too heavily on visual suggestion. What he calls a staircase may be a fractured slope. What appears to be a carving may be the result of rock weathering. Without tools, ceramics, or inscriptions, the claim of intentional design remains speculative.

Archaeology remains cautious

Most professional archaeologists have kept their distance from the site. It isn’t recognized as a cultural heritage location by the Japanese government, and no formal excavation has ever taken place. The formation sits in open water and can only be reached by dive, which adds to the challenge.

The lack of artifacts matters. When people build something, they tend to leave things behind, tools, bones, broken pottery, ash from fires. At Yonaguni, none of that has turned up. The stone shows no clear signs of being carved or shaped. There are no post holes, no channels, no surfaces smoothed by repeated use.

Because of this, many archaeologists see the formation as a case of pareidolia. It’s natural to spot patterns, especially ones that look familiar, even when they aren’t intentional. The site may look impressive, but without hard evidence of human involvement, archaeology has nothing to work with. For now, the discipline stays neutral.

Cultural memory and modern myth

Over time, the site has become a magnet for alternative theories. Some writers link it to the legend of Mu, a hypothetical lost continent in the Pacific. Others connect it to flood myths or undocumented ancient civilizations. These claims, while popular online and in documentaries, are not grounded in research.

Local oral traditions in the Ryukyus do not mention a sunken city off Yonaguni. There are no stories of cataclysm or disappearance tied to the location. The connection to Mu is a modern invention, often used to dramatize the mystery.

Still, the monument holds a grip on the imagination. Its size, setting, and silence make it compelling. It sits just beneath the surface, visible to anyone who makes the short boat trip and the short dive. The ease of access invites speculation. The lack of resolution keeps the story open.

What the site tells us now

No matter how it formed, the underwater structure off the coast of Japan shows just how easily we look for meaning in what we see. Sharp lines and flat terraces suggest intention, and the mind fills in the rest. Without artifacts or written records, people bring their own interpretations. Some see architecture. Others see geology.

The site has become a reminder of how little we can say for sure without evidence. There’s been no excavation, no datable material, and no tools or remains. Still, the debate hasn’t stopped. What keeps it going isn’t proof. It’s curiosity.

Some researchers still call for closer study. Others are convinced the explanation is already in front of us. Divers continue to visit, cameras still capture the edges, and the conversation never really fades.

The structure remains where it was found, just beneath the surface, shaped by water and time. Whether it’s a rare geological formation or the last trace of something older, it sits in silence, offering no answer.