On June 17, 1908, in the sky over a sparsely populated area of the taiga, near the Podkamennaya Tunguska River, a powerful explosion thundered. In most cases, the Tunguska event is said to have been caused by a meteorite but as you may guess, the whole event is shrouded in mystery even though it was massive.

The blast wave was so powerful that it was recorded even on the opposite side of the globe. For hundreds of kilometers from the epicenter of the explosion, trees were tumbled down, glass in the windows was smashed, people were knocked down.

According to modern estimates, the explosion power could reach 50 megatons – only slightly less than that of the “Tsar Bomba”, the explosion power of which was 58.6 megatons.

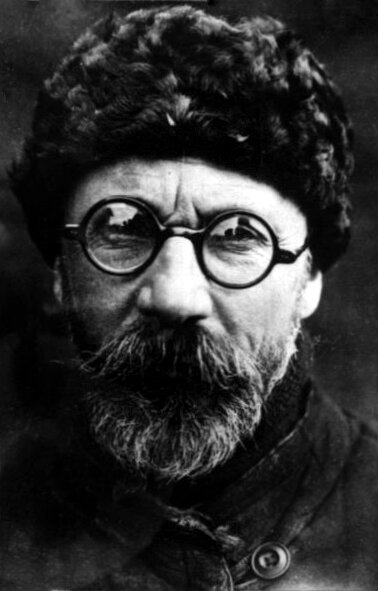

At the moment, the main hypotheses are a comet or meteorite. Unfortunately, the first research expeditions after the Tunguska Event set off to the place of the supposed impact site an entire 19 years after the events. The first expedition was headed by the scientist-mineralogist L.A. Kulik. In total, he organized four expeditions to the area of the meteorite impact site from 1927 to 1938.

During the expeditions, it was possible to establish that indeed in 1908, a meteorite entered the Earth’s atmosphere, which eventually exploded at an altitude of about 5-10 kilometers above the basin of the Podkamennaya Tunguska River.

The location of the epicenter of the explosion was established quite reliably, and different methods of determining the location of the explosion give almost identical results.

In this case, the crater from the fall of the meteorite was not found. This, in general, is not unusual. Meteorites falling in the atmosphere leave craters only if they reach the surface safe and sound, without having time to slow down.

In the case when the meteorite collapses when falling, the fragments usually slow down rather quickly in the atmosphere and fall to the Earth at speeds up to 200 m/s, or even slower. Of course, the debris falling at such speeds does not leave any craters.

Therefore, if after the destruction of what happened at an altitude of several kilometers, the Tunguska meteorite disintegrated into small fragments, then there should not be any crater. Some time ago, foreign scientists suggested that the nearby Lake Cheko could be a crater from a meteorite fall.

This is supported by the conical bottom shape, which is completely uncharacteristic for natural lakes and is characteristic of crater lakes. However, studies by Russian scientists helped to unequivocally establish that the lake is at least 8 thousand years old.

Unfortunately, despite the huge amount of work done during the expeditions, meteorite matter was not found during the search. Kulik’s expeditions in the area of the fall of the Tunguska meteorite discovered magnetite and silicate balls, which, judging by the results of the analysis and the high content of nickel, may well have an unearthly origin, but their connection with the Tunguska meteorite is doubtful: such balls from time to time are found in rocks of other regions of the Earth…

Is it strange that the fragments were not found? Not really. First, from the fall to the first expedition, a gigantic period of 19 years passed. The meteorite could be composed of loose material with a low density. Examples of such asteroids are well known, for example, object (29075) 1950 DA, which is a flying pile of rubble.

Fragments of such an object could well collapse over time from erosion and weathering. Academician Vernadsky generally hypothesized that the Tunguska meteorite was a lump of stuck together cosmic dust.

Secondly, the main efforts of Kulik’s expedition focused on searching for the crater, since one of the first messages contained information about a hot meteorite sticking out of the ground. It was later established that the message was false, but it sent Kulik on the wrong track.

The search for fragments of the meteorite should have been in the area of the epicenter of the explosion since when the meteorite collapses, its fragments very quickly lose speed and should fall nearby.

Thirdly, the terrain in the epicenter area is swampy, which made the search very difficult. A significant part of the fragments could well have plunged into the soft swampy soil, and 19 years of erosion and precipitation have reliably walled them up under the surface.

And besides, in those years, such science as meteorics was in fact just incipient and Kulik had neither the equipment available now, nor modern methods of searching for meteorites.

It is noteworthy that immediately after the fall of the meteorite, some Evenks living in those regions reported the finds of ferruginous debris in the area of the meteorite fall, but Kulik’s expedition could not confirm or refute these reports.

Unfortunately, the war interrupted L.A. Kulik, who died in 1942 after being captured by the Germans. In the postwar years, research was resumed only in the late 50s – early 60s, i.e. half a century after the fall of the bolide, however, they also did not bring results in the form of the found meteorite matter.

Analysis of the substance from peat bogs in the vicinity of the fall of the Tunguska bolide showed the presence of substances characteristic of some types of meteorites, however, the dating of the peat layers in which these substances were found is currently disputed and probably belong to an earlier period.

Do we know what the Tunguska Event was in the end?

At the moment, there are more than 100 hypotheses about what actually exploded in the sky over Tunguska, from completely fantastic, like a wrecked alien ship or Nikola Tesla’s experiments on transferring energy at a distance, to more or less adequate and entitled for existence.

At the moment, as a rule, two main hypotheses about the Tunguska event are being considered: cometary and meteorite, with most scientists leaning towards the cometary hypothesis. All the stories and descriptions of eyewitnesses fit very well into both these versions: the described behavior of the fireball corresponds very closely to how a falling large meteorite or comet should behave.

Comets are composed mostly of ice, which perfectly explains why fragments of meteorite matter have not been found. The weakness of the cometary hypothesis is the complete absence of any messages from astronomers about an approaching comet. It is quite possible that new expeditions to the site of the explosion will finally make it possible to discover the remnants of meteorite matter and shed light on what the Tunguska Event really was.

Join the discussion and participate in awesome giveaways in our mobile Telegram group. Join Curiosmos on Telegram Today. t.me/Curiosmos

Sources:

Hogenboom, M. (2016, July 07). Earth – In Siberia in 1908, a huge explosion came out of nowhere. Retrieved December 01, 2020, from http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20160706-in-siberia-in-1908-a-huge-explosion-came-out-of-nowhere

Root. (2019, October 02). 1908 SIBERIA EXPLOSION: Reconstructing an Asteroid Impact from Eywitness Accounts. Retrieved December 01, 2020, from https://www.psi.edu/epo/siberia/siberia.html

The Tunguska Impact–100 Years Later. (n.d.). Retrieved December 01, 2020, from https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2008/30jun_tunguska

Weisberger, M. (2020, May 26). Meteor that blasted millions of trees in Siberia only ‘grazed’ Earth, new research says. Retrieved December 01, 2020, from https://www.livescience.com/tunguska-impact-explained.html

When the sky exploded: Remembering Tunguska. (n.d.). Retrieved December 01, 2020, from https://earthsky.org/space/what-is-the-tunguska-explosion