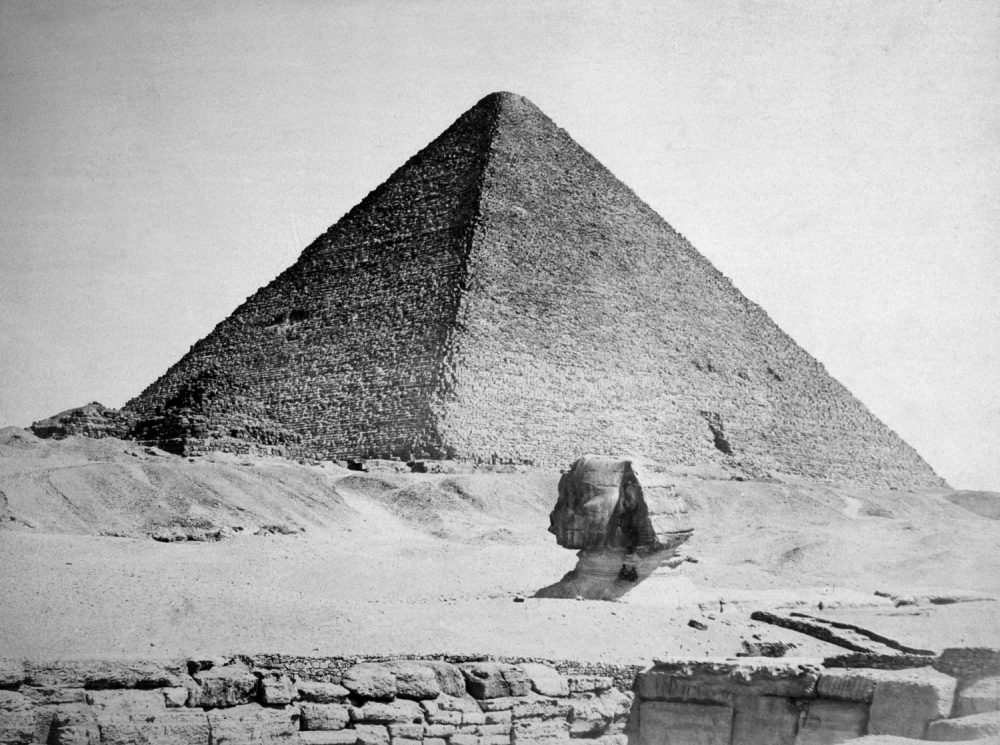

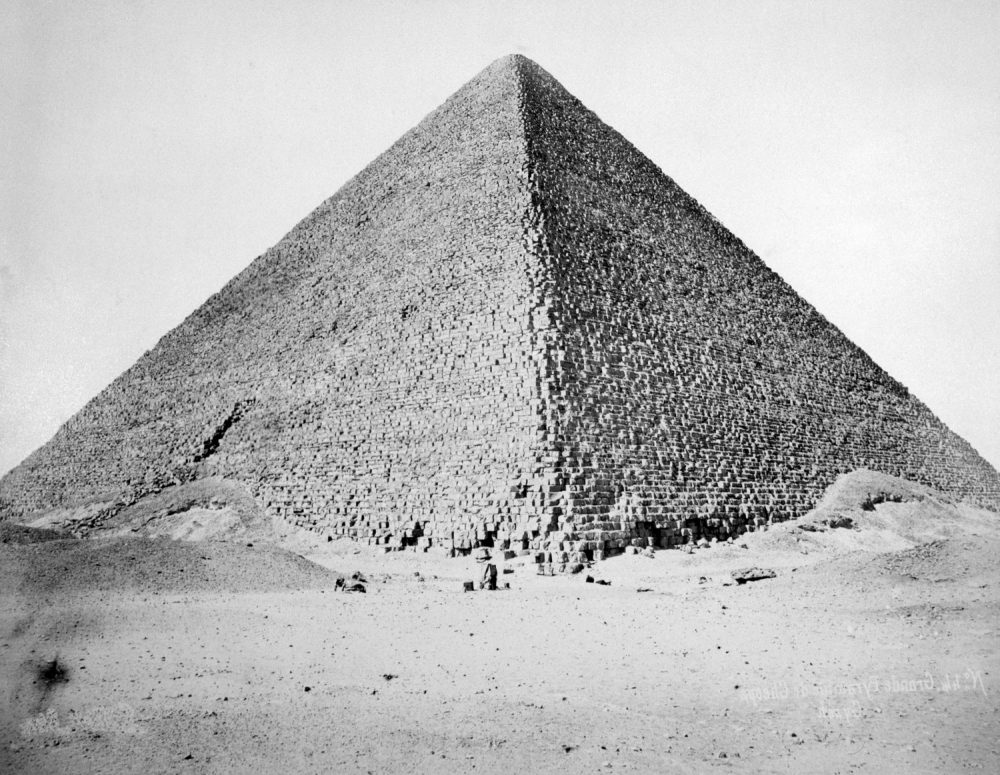

Although not the oldest and largest pyramid on Earth, the Great Pyramid of Giza, also known as Khufu’s pyramid, is certainly the most famous of all pyramids. Located at the Giza plateau, it is one of the three pyramids that have stood the test of time, accompanied by a mysterious statue whose origins are perhaps as mysterious as the pyramids. For centuries experts have wondered how it was possible for the ancient Egyptians to build these massive structures. Despite studying it for centuries, we have not managed to crack its biggest secret and answer “How was the Great Pyramid of Giza built?”

What kind of technology was used for quarrying the stones? How did they transport them once quarried? How did they transport them to the construction site? It is an impressive feat knowing that some of the stones used in the construction of the Pyramid were transported from quarries located more than 800 kilometers away. And how on Earth did they stack around 2.3 million stones weighing on average 3 tons and complete what would later become the only standing ancient wonder of the world?

How was the Great Pyramid of Giza built?

The pyramid’s construction is estimated to have started around 2580 BCE and was finished around 2560 BCE. During the construction, the pyramid builders used approximately 144,000 casing stones that were polished and flat to an accuracy of 1/100th of an inch, about 100 inches thick, and weighing approximately 15 tons each.

More than 4,500 years ago, its builders erected the most accurately aligned structure on the planet’s surface, facing true north with only 3/60th of a degree of error. Experts estimate that as many as 5.5 million tons of limestone, 8,000 tons of granite (imported from Aswan), and 500,000 tons of mortar were used to construct the Great Pyramid.

The effort

This means that much effort was put into building the pyramid. Yet mysteriously, archeologists have found neither blueprints nor designs that would help us understand how the ancients did it. This is strange because the ancient Egyptians were excellent scribes and were even greater history keepers. It makes no sense that they didn’t document their work.

After all, they built one of the most impressive buildings on the planet’s surface. But although we haven’t found documents detailing the great pyramid’s building process, archeologists have excavated quite a few things that may help us solve the puzzle on our own.

A Town of Pyramid Builders

So who built the pyramids? Was it slaves, as many scholars have maintained in the past? Or was it a Pharaonic workforce? If you chose the latter, then you are correct. Evidence of a massive town of pyramid builders was revealed in an archeological explanation that has helped us understand a small part of the process that involved building the pyramid.

During Channel 4′ TV series Egypt, Great Pyramid: The New Evidence, archeologist Mark Lehner reveals a discovery made by his team in the footsteps of the pyramid. The researchers uncovered the ancient remains of a long-lost town they say was once used as an ancient Egyptian port. Lehner revealed that the excavations yielded evidence of the layout of a small city where people who participated in the pyramid’s construction lived.

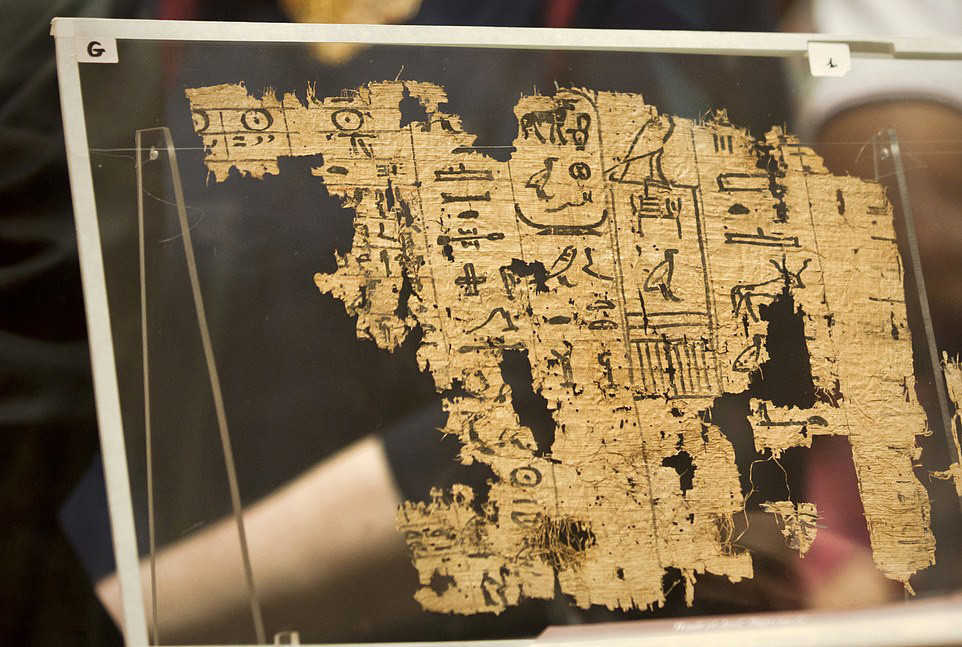

A 4,500-Year-Old Papyrus

As I’ve explained before, there is a complete lack of written sources that mention the building of the Great Pyramid. Nothing archaeologists have discovered so far can help us understand the entire process as it unfolded more than 4,500 years ago.

Nonetheless, we have made a few findings that indirectly speak of the construction process of the pyramid. Or at least, that’s what archeologists agree upon. One such discovery was the Diary of Merer, a Papyrus logbook believed to have been penned down more than 4,500 years ago, that records the daily activities of stone transportation from the Tura Limestone quarry to the Giza plateau, where the Great Pyramid stands.

The Diary of Merer, composed of Papyrus Jarf A and B, was discovered in 2013 by a French archeological mission led by Pierre Tallet of Paris-Sorbonne University in a cave in Wadi al-Jarf. The diary revealed that Merer was a middle-ranking official during the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt. Merer wrote down the activities daily spanning several months of work, involving the transportation of stones from Tura to Giza. This ancient Papyrus is also the oldest ever discovered.

Although the dairy does not directly say the limestone blocks were used in constructing the great pyramid of Giza, Tallet argues that the stones were most likely used for cladding the outside of the Great Pyramid. Here’s a small part of the diary of Merer translated into English:

First day : […] spend the day […] in […].

[Day] 2: […] spend the day […] in? […].

[Day 3: Cast off from?] the royal palace? [… sail]ing [upriver] towards Tura, spend the night there.

Day [4]: Cast off from Tura, morning sail downriver towards Akhet-Khufu, spend the night.

[Day] 5: Cast off from Tura in the afternoon, sail towards Akhet-Khufu.

Day 6: Cast off from Akhet-Khufu and sail upriver towards Tura […].

[Day 7]: Cast off in the morning from […]

Day 8: Cast off in the morning from Tura, sail downriver towards Akhet-Khufu, spend the night there.

Day 9: Cast off in the morning from Akhet-Khufu, sail upriver; spend the night.

Day 10: Cast off from Tura, moor in Akhet-Khufu. Come from […]? the aper-teams?[…]

Day 11: Inspector Merer spends the day with [his phyle in] carrying out works related to the dyke of [Ro-She] Khuf[u …]

Day 12: Inspector Merer spends the day with [his phyle carrying out] works related to the dyke of Ro-She Khufu […].

Day 13: Inspector Merer spends the day with [his phyle? …] the dyke which is in Ro-She Khufu by means of 15? phyles of aper-teams.

Day [14]: [Inspector] Merer spends the day [with his phyle] on the dyke [in/of Ro-She] Khu[fu…].

[Day] 15 […] in Ro-She Khufu […].

Day 16: Inspector Merer spends the day […] in Ro-She Khufu with the noble? […].

Day 17: Inspector Merer spends the day […] lifting the piles of the dy[ke …].

Day 18: Inspector Merer spends the day […]

Day 19 […]

Day 20 […] for the rudder? […] the aper-teams.

A 4,500-Year-Old Ramp Contraption

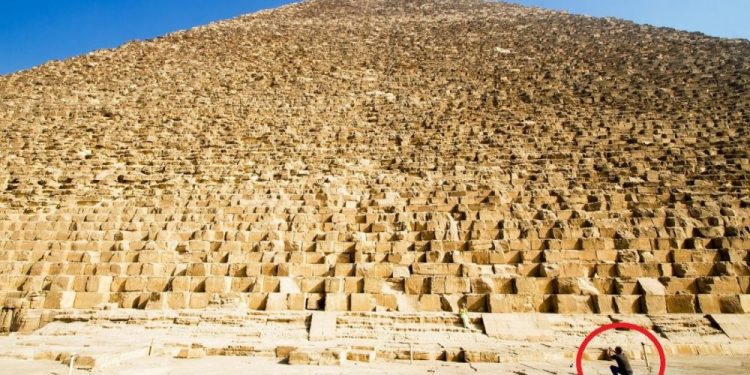

Another stunning discovery may hint at how the Great Pyramid of Giza was made at a site called Hatnub, an ancient Egyptian quarry located in the Eastern Desert of Egypt. In 2018, a French archeological mission discovered a contraption that may have been used to transport massive alabaster stones up a steep ramp.

“This system is composed of a central ramp flanked by two staircases with numerous post holes,” Yannis Gourdon, co-director of the joint mission at Hatnub, told Live Science. “Using a sled which carried a stone block and was attached with ropes to these wooden posts, ancient Egyptians could pull up the alabaster blocks out of the quarry on very steep slopes of 20 percent or more.”

Essentially, the ropes attached to the sled would multiply the force, making pulling the sled up the ramp easier. The discovery is so unique that experts have revealed that this transportation system has never been discovered anywhere else. But how did the archeologists know it may have been used to build the pyramid?

The study of the tool marks and the presence of two [of] Khufu’s inscriptions led us to the conclusion that this system dates back at least to Khufu’s reign, the builder of the Great Pyramid in Giza,” explained Roland Enmarch, one of the directors of the archaeological mission.

The researchers further revealed that since the transportation system dates back to at least the reign of Pharaoh Khufu, they already have the necessary technology to transport massive blocks of stone, using extremely steep slopes. In other words, they may have used this system to help them transport the massive stones and build the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Have something to add? Visit Curiosmos on Facebook. Join the discussion in our mobile Telegram group.