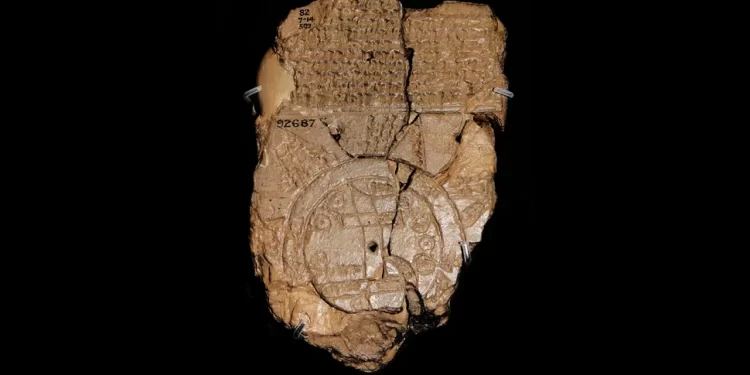

Imagine looking at a map that dates back over 2,500 years, showing how the ancient Babylonians viewed their world. The Babylonian Map of the World, known as “Imago Mundi“, is the oldest known map of its kind, offering a remarkable peek into the mindset and geography of ancient civilizations. Inscribed on a small clay tablet, this map showcases how the Babylonians perceived their surroundings and is a true treasure of ancient cartography.

What Is the Babylonian Map of the World?

This tablet, about the size of a modern smartphone at 4.8 inches tall by 3.2 inches wide (12.2 by 8.2 cm), was discovered in Abu Habba (also known as Sippar), an ancient Babylonian city in modern-day Iraq. Created around the sixth century B.C., it’s a fascinating depiction of how Babylonians understood the world thousands of years ago.

Instead of the sprawling continents and oceans we see on maps today, the Babylonian map presents the world as a simple disc surrounded by a circular body of water called the Bitter River. At its heart is the Euphrates River and, of course, the city of Babylon, which was a central hub of Mesopotamian civilization. The map’s locations are labeled in cuneiform, the wedge-shaped writing used by the Babylonians.

Interestingly, the mapmakers didn’t worry too much about perfect accuracy. For instance, Babylon is only marked on one side of the Euphrates River, even though it spanned both banks. This suggests that the map wasn’t about geographical precision, but rather a symbolic representation of the world.

A Story Told Through Cuneiform

What makes the Babylonian Map of the World so intriguing isn’t just its function as a geographic tool—it’s also a window into the myths and beliefs that shaped how ancient Babylonians understood their universe. Above the map, a block of text recounts the creation of the world by Marduk, the powerful chief god of Babylonia. For the Babylonians, Marduk wasn’t just a creator but a divine ruler who imposed order on chaos, making the universe habitable. The inscription includes references to animals familiar to Babylonians, like lions, mountain goats, and leopards, but it also mentions mythical figures such as Utnapishtim, a king who survived a great flood—a story with striking parallels to the tale of Noah from the Bible.

But the magic of the map doesn’t stop there. On the back of the clay tablet, additional text describes eight distant regions—referred to as nagu—each with brief, tantalizing descriptions. These places, shrouded in mystery, extend beyond the known world and reflect Babylonian speculation about far-off lands. Whether these regions were based on real locations or purely mythological constructs, they show that Babylonians had a vivid imagination and were fascinated by lands that lay beyond their borders. The map offers more than geography—it provides an early glimpse into how ancient civilizations conceptualized the unknown and turned it into part of their mythology and worldview.

Today, this ancient map is housed at The British Museum, where it remains a permanent part of their collection—a reminder of how ancient peoples sought to make sense of the vast world around them.